An Old Book on the Sani-Yi Minority

One may wonder whether it makes any sense to read, in the first decades of the 21st century, a book written at the end of the 19th. Clearly, the person who has spent some of their time translating it, revising it, updating the old names into modern spelling, and editing it as a book, is going to answer affirmatively. Therefore, that answer holds no weight unless backed up with some reasons.

The first and most obvious reason is that this short book, although titled “The Lolos”, is the first and only monograph existing in any Western language on the branch of the Yi people known today as the Sani, who call themselves gni, as already noted by Paul Vial. That is, since the writing of this book, no further book-length study of the Sani has been published in any Western language.

The second reason is that, being a book published in French, it has gone almost unnoticed by researchers in other countries, who, as usual, search for study materials in English. This is a major oversight in the case of Yunnan, where French authors of the late 19th and early 20th centuries provided extremely valuable material on the life and society of Yunnan’s inhabitants—both Han Chinese and minorities. Especially interesting are the chronicles of missionaries who, despite being steeped in a paternalism that would now be considered unacceptable and a colonial mindset they cannot quite hide even in their most well-meaning writings, provide firsthand material about the life and culture of those peoples due to the many years they lived among them.

Third, the book itself presents very interesting material. In fact, some of the cultural and religious descriptions provided by the author have barely been studied since. Some of them may help us understand cultural concepts among the Yi and related peoples that have seen little research since Vial’s time.

It’s clear that this work needs to be read contextually, with an awareness of the author’s perspective—a very particular kind of missionary who believes he has found among the Gni a people isolated from Chinese influences, ready to receive Catholic teachings, and who sees himself offering his life for the salvation of the Yi people’s souls. The historical context must also be considered: while China’s last dynasty, the Qing, was crumbling—bringing down with it the imperial regime that had shaped China for the last 2,000 years—France was growing more secular, and missionary work was increasingly viewed with skepticism. Moreover, France and China had clashed in the Franco-Chinese War of 1884–85, which granted France an «influence zone» in Yunnan, Guangxi, and southern China.

That war is key to understanding why Chinese people were often unfriendly toward French missionaries, and why those missionaries showed little sympathy toward the Han Chinese in turn. This also explains why many missionaries focused on evangelizing minority populations, who tended to be more receptive.

In that sense, Vial’s humility is striking. His writing is so succinct it sometimes seems like he’s apologizing for lingering on a topic, as though he feared the reader might get bored—as though the life, culture, and religion of the Lolo/Gni/Sani would interest no one.

Of particular value is his brief, unfortunately less than a page-long, description of the Sani pictographic script, as well as the bilingual Sani–French edition (which we have preserved in this edition, translating it below the original) of the people’s main myths: the Creation of the World, the Great Drought, and the Flood.

One of the hardest paradigms to justify in 20th-century anthropology is the idea that descriptive studies of human communities are no longer worthwhile. That kind of work was considered a thing of the past—even though many peoples, such as the one this book covers, still lack any descriptive study of their society. This led to the absurd situation in which anthropologists and historians continually refer to human entities for which there is no documentation clearly defining who they are or what their core cultural features might be. And the excuse that societies are always changing doesn’t help here: we can, at the very least, describe what a society was like at a given moment.

In China, an attempt was made to overcome this gap through major foundational collections of knowledge on the national minorities. But since these were organized around the officially recognized nationalities (55 minorities plus the Han majority), and since many of these nationalities include highly diverse ethnic groups, it’s impossible to distinguish the defining features of each sub-group or ethnic branch.

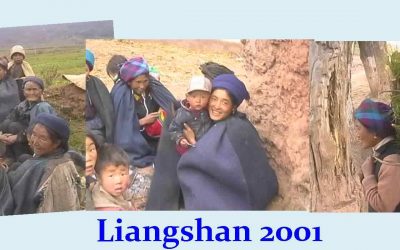

There are, indeed, some historical and anthropological studies in Chinese focused on the Sani, and thankfully they are increasing in number—partly due to the Sani’s visibility, living as they do near one of Yunnan’s most popular tourist sites, the Stone Forest. They have become part of the collective image of traveling to Yunnan, with their colorful hats and serious blue vests, the large guitars the men dance with, and the women’s frequent, spontaneous dances.

Vial’s book also became a reference point for later linguistic and anthropological research in Yunnan and southern China more broadly, and some of his claims were hotly debated by researchers of the time.

For all these reasons, I believe it’s still important to make the words of someone who knew and loved the Sani almost 150 years ago accessible today.

To make this book easier to read for 21st-century readers, we’ve made the following changes:

- All Chinese names have been converted to pinyin for easier reading.

- We’ve clarified some of the more obscure concepts in the original narration, distinguishing Paul Vial’s own notes (marked as N. del A.) from our modern explanatory notes (marked as N. del T. or sometimes unmarked).

This edition also includes the short text The Spirit and the Heart among the Lolos, published in 1905, which offers a firsthand view of how Vial saw his love for the Lolos and how those close to him perceived it. It also contains a translation of the myth The Origin of the Rainbow, which heavily influenced his research on Sani culture. The book also includes a translation of the first ethnological description of the Yi: The Lolos by François Louis Crabouillet.

We hope the effort has been worth it.

This is the introduction to the book: Paul Vial, Paul. Los Lolos: Historia, religión, costumbres, lengua, escritura Edited, translated and annotated by Pedro Ceinos Arcones

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China). Yo can see my mis videos in Youtube, and more pictures about China in Instagram (pedroyunnan).

In travel, I have specialized in Yunnan, Tibet, the Silk Road, and other lesser-known places. Feel free to write to me if you’re planning a trip to China. The agency I collaborate with offers excellent service at an unbeatable price. You’ll find my email below.

Last posts

The first description of the Religion of the Yi

The first description of the Religion of the Yi By Father François Louis Crabouillet in 1872. The religion of the Lolos[i] is that of sorcerers: it consists only of conjurations of evil spirits, according to them, the only authors of evil. Without being devout like...

History of Dunhuang, crossroads of cultures on the Silk Road

History of Dunhuang, crossroads of cultures on the Silk Road Dunhuang is one of the most fascinating cities on the Silk Road, although it now appears to be asleep, in the sleep that the improvement of communications in recent centuries has brought to the great...

Kyzil Grottoes – Primitive Buddhist art on the Silk Road

The Kyzil Grottoes - Primitive Buddhist art on the Silk Road The Kizil Grottoes are located on the cliffs of Minya Dag Mountain facing the Muzhati River, 7 km southeast of Kizil Township, Baicheng County, and about forty-three kilometers west of present-day Kucha,...

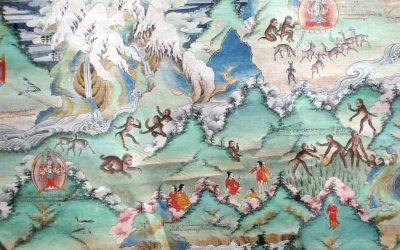

Tibetans, the people who descend from the monkey

Tibetans, the people who descend from the monkey According to an ancient myth, the Tibetans originated from the union of an ogress (raksasi) and a monkey. The monkey was sent by Avalokitesvara, Mother Buddha, to sow the seed of Buddhism in these lands. One day, an...

All you need to know about the ox in the Chinese horoscope

All you need to know about the ox in the Chinese horoscope The ox is a very beloved animal among the Chinese, despite its size, it is tame and peaceful, often in the villages, it is the youngest children who take it to the field to play, it rarely acquires the fierce...

The snake in the Chinese horoscope

The snake in the Chinese horoscope The snake is an ambiguous animal in the collective image of the Chinese people. On the one hand, it is considered similar to the dragon. Many Chinese authors recognize that the dragon, nonexistent, is nothing more than the...