The Bull that Shaped the World and Other Sacred Bovines among the Bulang Minority

The Bulang people (布朗族), an Austroasiatic ethnic group primarily inhabiting Yunnan’s tea-growing highlands, revere the ox as a sacred being intertwined with creation, agriculture, and spiritual power. The ox appears in their myths, agricultural rituals, festivals, and social customs, representing strength, prosperity, and spiritual connection. The Bulang’s ox traditions are uniquely tied to tea cultivation, cosmic order, and ancestral blessings.

In the Beginning, There Was the Ox

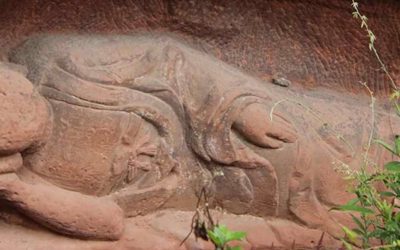

Among some Bulang, the ox is considered a sacred animal that helped in creation or provided sustenance to early humans. The creation myth Gumiye tells of a big ox that created everything that exists in this world. After the creation was completed, he used his four legs to keep the heaven stable. In some versions, the ox plowed the earth with its horns, creating mountains and valleys, its sweat formed rivers, and its breath brought wind, allowing life to flourish.

The Ox and the Beginning of Agriculture

There are also tales that link the ox to the origins of agriculture. One legend tells of a heavenly ox that descended to earth carrying the first grains of rice or millet in its mouth (or dung). In another one, a Bulang ancestor followed the ox and discovered that where it rested, crops sprouted. In some others, the ox then taught people how to plow and sow, linking it to the origin of farming, or a divine or heroic ox teaches the Bulang people farming techniques, emphasizing the animal’s role in their transition from hunting to agriculture.

These myths explain why the ox has a central role in some rituals related to the traditionally swidden (slash-and-burn) agriculture. Its presence is especially important in the Plowing Ceremonies, performed before planting, when rituals are performed to honor the ox; and in Thanksgiving Festivals, after harvest, when Bulang communities express gratitude to the ox for its work. They decorate cattle, feed them special foods, and perform dances. In some places, the Ox Dance (牛舞) imitates ox movements, symbolizing fertility and strength.

The Ox and the Origin of Tea

Other myths relate it to tea. They tell of a demon (or drought spirit) that devoured crops until a sacred ox challenged it. The ox fought the demon for days, finally trampling it into the earth. Where the demon’s blood fell, the first tea plants grew. The ox then collapsed, and its body became a mountain that protected the village. Other versions state that after the battle, the people discovered that where an ox’s blood fell, the first tea plants appeared. The transformation of blood into tea is unique to the Bulang. Some of their tea fields are protected by oxen heads, and in some villages in Mengsong (勐宋) district, they perform ox sacrifices during tea-harvesting ceremonies, recalling the myth.

Spiritual Role of the Ox

The ox also has a sacrificial and spiritual role. Due to its ability to communicate with heavenly deities, it is sacrificed to honor ancestors or deities, believing that it will carry the prayers to the spirit world. Oxen are also central to other festivals. In New Year and Harvest Festivals, the ox is sometimes paraded or decorated. In some villages, an ox made of dough or straw is offered to ancestors, mirroring the cosmic ox’s sacrifice. In Xishuangbanna, the «Gangyong» (岗永) Festival includes a ritual ox sacrifice to pray for rain/harvest, tied to the demon-slaying myth. In Lincang, they have an Ox King Festival, held on the 8th day of the 4th lunar month (similar to Han Chinese Ox King festivals), which focuses on thanking oxen for labor—feeding them sticky rice and let them rest the whole day.

Ox bones are perceived as full of magical power, and they are used sometimes in traditional divination. There are no studies to ascertain if this was an independent development or could be related to the Oracle Bone divination practiced in China more than 3,000 years ago.

Conclusion

The ox in Bulang culture is more than just a farm animal—it embodies labor, sustenance, and spiritual connection. Its presence in myths, rituals, and daily life underscores its role as a symbol of resilience, prosperity, and communal harmony. Its economic and religious value makes the ox second only to people in Bulang symbolic thought. Owning cattle was historically a sign of prosperity among them, and oxen were used in trade or as bride prices in marriages.

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China). In my travels, I have specialized in Yunnan, Tibet, the Silk Road, and other lesser-known places. Feel free to write to me if you’re planning a trip to China. The agency I collaborate with offers excellent service at an unbeatable price. You’ll find my email below.

Last posts

The truth about the Great Wall

The truth about the Great Wall What would later come to be known as the Great Wall formed as a response to increased Mongol raiding after Esen was killed in 1455. Having failed to capitalize on the capture of Zhengtong, Esen lost the political momentum that had held...

Buddhist Immersion from Shanghai: No Need to Board a Plane—Paradise Is Right at Your Doorstep

Buddhist Immersion from Shanghai: No Need to Board a Plane—Paradise Is Right at Your Doorstep Residents of Shanghai eager to learn more about Buddhist art and history often think they must undertake long journeys to reach the sacred mountains of this religion. What...

The Lost Mythology of Ancient China

The Lost Mythology of Ancient China Reconstructing the mythology of ancient China is a painstaking task that tries to characterize some legendary figures and situations based only on the few sentences about them found in later works by philosophers and historians. The...

How a Eunuch Was Created in 19th-Century China

How a Eunuch Was Created in 19th-Century China A wealthy eunuch would purchase a boy from a poor family. This boy had to be between seven and ten years old. He would be kept confined for two weeks and subjected to a very strict diet; he ate little. Use of...

Dunhuang in the Silk Road

Dunhuang in the Silk RoadDunhuang is a city in the middle of the desert. Over its 2,000-year history, it has always been the last Chinese outpost before reaching the Western Regions—those kingdoms more or less dominated by the imperial regimes, yet showing customs so...

Discover China’s Largest and Most Beautiful Salt Lake

Discover China’s Largest and Most Beautiful Salt Lake The development of tourism and transportation in China is bringing to light places that were previously very hard to access and virtually unknown. Some of these destinations are beginning to gain a certain...