What if modern science originated on the Silk Road?

In one of his most striking works, Warriors of the Cloisters: The Central Asian Origins of Science in the Medieval World, Christopher Beckwith, as the title of the work indicates, proposes that modern, Western science owes its origin to a series of cultural initiatives that developed on the Silk Road, mainly in the ancient kingdom of Bactria, now outside the Chinese border, in the territory of Tajikistan. The two institutions referred to are the original universities, as centers of continuous transmission of knowledge among citizens specifically dedicated to studying, and the method of recursive argument, which was the scientific method of the Middle Ages in Europe. They were created in the times when the kingdoms of the Silk Road were important centers of Buddhist study and debate, being later adapted, as far as possible, to the society created after the Muslim invasions, and transmitted to Europe before disappearing in their place of origin due to religious pressure.

Beckwith asserts that modern science is directly descended from medieval science and that this, in turn, underwent a revolution when, under Arab influence, the two aforementioned scientific institutions arrived in Europe.

As for the institutions of higher education, he assures that in spite of the authors who consider the «college», precursor of the university, as an entity that developed autonomously in Europe, there is no evidence of its existence before the first one was founded in Paris in the year 1180, by a person returning from the crusades in Jerusalem. This return trip, which would have obliged him to cross Syria, would have brought him into contact with the Islamic madrasas, authentic teaching centers at that time specifically oriented to the study and maintenance of the students. On the other hand, it is already known that the Islamic madrasas had originated on the Silk Road a few centuries earlier and that their architectural structure, their function, and their integration into society as a whole and into the world of knowledge, in particular, are heirs of the Buddhist viharas, also created in these same lands. The chronicles relate that when a vihara was founded, a village and its inhabitants were assigned to it for its sustenance.

As for the method of recursive argument, its origin, undoubtedly in the same geographical area, is doubtful as to its intellectual genealogy. Beckwith considers that it may have had influences from ancient Greek philosophy (let us not forget that for centuries these lands were ruled by the Hellenistic kingdoms that succeeded the conquests of Alexander the Great), as well as local philosophical conceptions. As Beckwith points out «The great importance of the method for science is its formal, overt structure, its most salient characteristic, which impels the author to examine a question from all directions, including hypothetical ones, drawing attention to the unknown, and encouraging speculation on possible alternative solutions to problems».

The last part of his book is devoted to analyzing the reasons why, being both institutions also known in the Arab world, India and China, they only generated a revolution of thought in the West, which would respond to the application of the scientific ideas proposed by Aristotle, rescued from oblivion some and commented on others by Arab philosophers, such as Avicenna, which led to a scientific attitude towards all the events of knowledge, and in turn to the development of modern science.

If the importance of the Silk Road kingdoms in the cultural development of China has already been evident for some decades, first in the transmission of the bronze culture and the domestication of cattle and sheep from the West, then in the transmission of Buddhism, which is no longer Hindu but Central Asian, and later in the transmission of traditions that are no longer Hindu but Central Asian, and later in the transmission of artistic traditions, from painting and sculpture to music and theater, developed locally, Beckwith’s essay invites us to re-evaluate the importance of these small but not isolated kingdoms in the development of the great cultures of our planet: specifically those of China, India, the Arab World, and Europe.

For more information: Beckwith, Christopher. Warriors of the Cloisters: The Central Asian Origins of Science in the Medieval World. Princeton University Press, 2012.

Last posts

Dunhuang in the Silk Road

Dunhuang in the Silk RoadDunhuang is a city in the middle of the desert. Over its 2,000-year history, it has always been the last Chinese outpost before reaching the Western Regions—those kingdoms more or less dominated by the imperial regimes, yet showing customs so...

Discover China’s Largest and Most Beautiful Salt Lake

Discover China’s Largest and Most Beautiful Salt Lake The development of tourism and transportation in China is bringing to light places that were previously very hard to access and virtually unknown. Some of these destinations are beginning to gain a certain...

A Giant Mandala in the Heart of Tibet

A Giant Mandala in the Heart of Tibet The Palkor of Gyantze is one of Tibet’s great marvels and a unique jewel of universal architecture and art. Its shape, scale, and iconography defy comparison with any other construction. Amidst some of the highest mountains of...

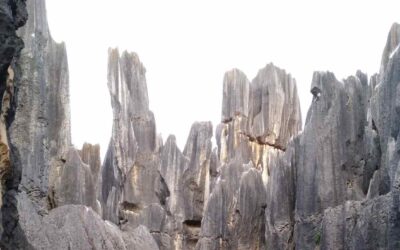

The Stone Forest: A Natural Wonder Just a Step Away from Kunming

The Stone Forest: A Natural Wonder Just a Step Away from Kunming The Stone Forest (石林) is the star attraction in the Kunming area. Located 86 kilometers from the city, it is an extensive labyrinth of sharp limestone pinnacles, some reaching up to thirty meters in...

Chinese Herbal Medicine Shop in Weishan, Yunnan

Chinese Herbal Medicine Shop in Weishan, Yunnan China still maintains a strong tradition of using natural medicines, specifically herbs with medicinal properties that have been used for centuries. In addition to being present in the composition of many modern...

Kunming Scenes 2025-feb

The World of Noodles If the variety of wheat or rice noodles found in China is already enough to fill an entire book, an appendix should be dedicated to noodles made from other ingredients. It seems that any vegetable that can be turned into flour only needs a bit of...