Taishan Mountain, life and death in Chinese culture, according to the work of Edouard Chavannes

Mountains are, in China, divinities. They are considered as nature powers who act in a conscious way and who can, therefore, be made favourable by sacrifices and touched by prayers; but these deities are of various importance: some are small local geniuses whose authority is exercised only on a small territory; others are majestic sovereigns who hold immense regions under their dependence. The most famous are five (1); they are: the Song Gao or Central Peak, the Taishan or Eastern Peak, the Hengshan or Southern Peak, the Huahan or Western Peak, the Hengshan or Northern Peak. Among these five mountains themselves, there is one that is even more famous than the other four; it is the Taishan or Eastern Peak (pp 3)

Folklore also teaches us that the mountains are the habitat of characters endowed with marvellous faculties; ╓6 fairies or gnomes have their frolics there. In China, under the influence of Taoism, these geniuses of the mountains were conceived as men freed from all the obstacles that weigh down and shelter our existence; they are the immortals, the blessed to whom one who feeds on marvellous jade utensils and who drink ambrosia can go, as the inscriptions on three mirrors from the time of the Han say (pp. 6).

But the mountain is not only the place where the celestial gods and the immortals appear; it is itself a divinity.

The general attributions of a mountain deity are of two kinds: on the one hand, in fact, it weighs by its mass on the whole surrounding territory and is like the principle of stability; it is the regulator which prevents the ground from becoming agitated and the rivers from overflowing; it puts obstacles in the way of earthquakes and floods. On the other hand, the clouds accumulate around the mountain top which seems to produce them and which deserves the Homeric epithet of «assembler of clouds» (pp. 8).

Many prayers from the Ming period show us that the Taishan is indeed invoked by virtue of these two kinds of attributions. In the spring, it is implored to promote the growth of grain; in the autumn, thanksgiving is offered to thank it for the harvest it has protected. It is asked to help men by its invisible and powerful action which distributes rain and good weather in the right proportions and allows the nourishing plants to reach maturity. In case of drought, it is quite natural to turn to it, because «to see that the rain comes to the ploughman in good time is the secret task for which it is responsible»; so when the rains are late, the ears of corn in the fields wither and the peasants begin to fear famine, the sovereign of mankind has recourse to the majestic Peak, who can and must put an end to this misfortune (pp. 8).

Similarly, in the event of an earthquake or flood, prayers appropriate to the circumstances remind the Taishan of his functions as ruler of an entire region and invite it to restore order (pp 9).

Taishan is the Peak of the East; in this capacity it presides over the East, that is to say, the origin of all life. Like the sun, so all existence begins on the eastern side. The yang principle, which makes the sap in the green plants spring forth, is concentrated on the Eastern Peak, from which emanates its invigorating fragrance (pp. 12).

At the same time as the Taishan carries in its side all future existences, it is, by a rather logical consequence, the receptacle where the lives that have come to an end go. From the first two centuries of our era, it was a widespread belief in China that when men died, their souls returned to the Taishan. In popular literature, there are a whole series of anecdotes that inform us about these kinds of Champs Elysées where the dead continue to speak and act as if they were alive; official positions are sought there, recommendations to influential people are very useful; it is another underground China that flourishes under the sacred mountain (pp. 13).

Since the Taishan gives rise to births and collects the dead, it has been concluded that it presides over the greater or lesser duration of human existence; it unites in itself the attributions of the three Fates, giving life, maintaining it and finally interrupting it. Around the year 100 A.D., a certain Hiu Siun, feeling seriously ill, went to the Taishan to ask to live. A poet of the third century A.D. wrote with melancholy: «My life is on its decline; the Eastern Peak has given me an appointment” (pp. 13).

The cult of the Taishan because this divinity presides over the souls of the dead. This is why in China one finds representations of the torments of the underworld in two kinds of Taoist temples, one being those of the god of the city (Chenghuang miao), the others being those of the Taishan (Dongyue miao). This again explains why, in these two kinds of temples, one often sees, suspended above one of the doors or against a wall, some enormous abacus; the presence of this calculating machine means that the divinity of the place has the mission of counting human actions and balancing good and evil (pp 16).

Historical texts tell us at various times and at great length about the famous feng and shan ceremonies that were performed at the top and bottom of the Taishan. The feng sacrifice was for Heaven; the shan sacrifice was for Earth. It is important to determine precisely what these rites were (pp. 16).

Imagen shi zhao via Flick.

Chavannes, Edouard. Le T’ai Chan. Essai de monographie d’un culte chinoise. Ernest Leroux. Paris. 1910.

More posts on Chinese culture

The Horse God as One of the Most Popular Deities in China

The Horse God as One of the Most Popular Deities in China If a visitor goes to the Great Wall at Juyongguan, the section closest to Beijing and one of the most historically significant, and takes the time to explore the complex of structures carefully—a...

Geckos and the “Mark of Chastity” in Imperial China: History, Symbolism, and Cultural Context

Geckos and the “Mark of Chastity” in Imperial China: History, Symbolism, and Cultural Context Across the long span of imperial Chinese history, the gecko occupied a surprisingly prominent place in discussions of female chastity, bodily integrity, and the regulation of...

Why It Is Necessary to Study Suicide in Chinese Culture

Why It Is Necessary to Study Suicide in Chinese Culture While drafting new chapters for my Brief History of China, cases of suicide kept appearing in the most diverse circumstances. Ministers and wives who allowed themselves to be buried alive to accompany kings to...

The true origin of the Great Wall

The true origin of the Great wall, as seen in Nicola Di Cosmo (The Origins of the Great Wall. Silk Road Journal. 1993). Generally speaking, the political discourse about foreigners in pre-imperial China tends to justify expansion and conquest, which is exactly what...

Parnashavari: The Tibetan Goddess of Medicine

Parnashavari: The Tibetan Goddess of Medicine Within the complex symbolism of Tibetan deities and protectors, I like to look for distinctive details that allow us to identify a figure the moment we see them in a temple. One of the goddesses who makes this task...

The Smallpox Goddess (Doushen)

The Smallpox Goddess (Doushen) The Smallpox Goddess (Doushen 痘神) is part of a group of goddesses whose primary role was the protection of children. In the final years of the imperial era, they operated under the authority of Bixia Yuanjun, the daughter of the Emperor...

More posts on China ethnic groups

The Local Lords cult of the Bai nationality

The worship of the Local Lords (benzhu) is the most characteristic of the Bai people. Their religious life revolves around the Benzhu temple of each village, as each village venerates a local lord, sometimes a historical figure who sacrificed for the people. In other...

The tiger hero of the Naxi

The tiger hero of the Naxi[1] A long time ago, a man named Gaoqu Gaobo lived in the Baoshan area. He had a strong body, lively intelligence, and certain magical powers. He was always willing to help people. One day he went on a trip with a group of villagers. After a...

Wonderful- yaks most precious treasure is their manure

Wonderful- yaks most precious treasure is their manure Most of the travelers who visited Tibet in former times noticed the importance that, for the maintenance of the living of the Tibetan nomads and travellers, had the Yak manure, known among the...

Life of Milarepa, the hermit poet

Life of Milarepa, the hermit poet. MiIarepa is one of the most beloved religious leaders of Tibet. His story, full of unique facts, has been told again and again over the centuries, and if the publishers did not warn that this is the autobiography written by the holy...

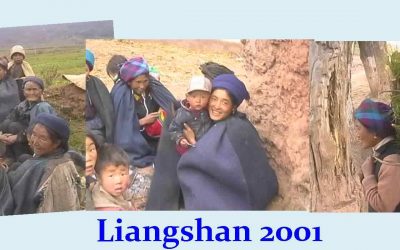

The first description of the Religion of the Yi

The first description of the Religion of the Yi By Father François Louis Crabouillet in 1872. The religion of the Lolos[i] is that of sorcerers: it consists only of conjurations of evil spirits, according to them, the only authors of evil. Without being devout like...

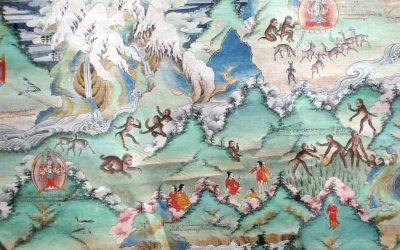

Tibetans, the people who descend from the monkey

Tibetans, the people who descend from the monkey According to an ancient myth, the Tibetans originated from the union of an ogress (raksasi) and a monkey. The monkey was sent by Avalokitesvara, Mother Buddha, to sow the seed of Buddhism in these lands. One day, an...