The Grand Canal and the Great Wall

In Brief: A brief review showing some of the similarities between the two iconic works of Chinese history and culture, their goals, and their differences. As well as how they both ended up shaping this country.

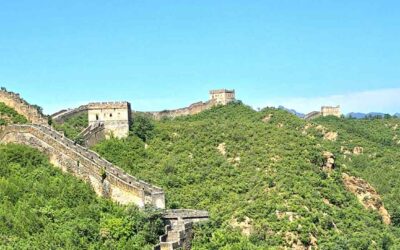

I have always been struck by the parallels between the two great wonders of Chinese engineering: the Grand Canal and the Great Wall. The Great Wall stretched along more than six thousand kilometers of China’s northern border, more or less effectively separating the agricultural lands of China proper from the nomadic territories populated by various nations of herders. The Grand Canal runs for 1,800 kilometers through the heart of the country, connecting, thanks to its waters, its main economic, political, and commercial centers. Thus, these two impressive works, unparalleled in the history of mankind, reflecting the ability of the Chinese people to complete tasks of cyclopean dimensions, show the two main impulses present in the formation of China: integration and separation.

While the Great Wall is the symbol of that separation between the Chinese culture, agricultural, sedentary, refined and urban, and those other nomadic cultures, always on the move, the Grand Canal is the symbol of the successful integration between the cultures of northern and southern China that will eventually form a country with well-defined common characteristics.

I think that the Grand Canal and the Great Wall are the warp on which Chinese civilization has been forged, the loom on which history has been shaping one of the most unique cultures of our planet because if it is already known that the Great Wall is the heir of the small walls that began to be built more than 25 centuries ago, in times of the Warring Kingdoms, and that in reality, far from being a single continuous line, it is a complex network of walls of more than 20,000 kilometers, the Grand Canal is the apotheosis of those small canals that from the same time began to shape the economy and politics of China; and linking its five major rivers, it is the main artery of a transportation network difficult to imagine.

The Grand Canal is the apotheosis of those small canals that from the same time began to shape the economy and politics of China and linking its five major rivers, it is the main artery of a transportation network difficult to imagine.

And just as the Great Wall is great as the major heir of the original walls that separated the Chinese world from the outside worlds, the Grand Canal is great as the culmination of the integration processes that during the previous centuries had been gradually bringing the populations of China closer together. Designed for conquest and trade, food production and distribution, for war and peace, the Grand Canal symbolizes the great integration, continuous communication, the construction of a national identity around those distinct cultures inherited from the traditions of the Warring Kingdoms. And especially of northern and southern China; of wheat and rice, meat and fish, toughness and sensitivity, yang and yin. Yes, the Grand Canal could well be the elegant line that separates and communicates the two opposing principles in the classic Taoist anagram.

It is no coincidence that the two great unifications of China have resulted in these two engineering marvels. And if that first unification of the First Emperor Qinshihuang left us the Great Wall, the second, carried out 700 years later by the Sui Dynasty (581-618), bequeathed to posterity the Grand Canal. It is also interesting to note that both works left the respective dynasties, and the people in general, so exhausted that shortly after the completion of their construction, these dynasties were overthrown by popular uprisings, enjoying instead the progress they brought, the dynasties that succeeded them: the Han Dynasty in the case of the Great Wall and the Tang in the case of the Grand Canal. Being the Han and Tang dynasties precisely those that molded the soul of China.

For greater parallelism, these two great works were decisive to the end of these dynasties, and thus, after the death of Qinshihuang, the trap set for his legitimate heir, destined to the Great Wall, led him to suicide, giving way with him to the reign of his weak brother, and eventually to the end of the dynasty. Emperor Yang himself of the Sui dynasty, builder of the Grand Canal, would die in Yangzhou, at the end of an inspection tour of it. This is the second chapter of my book: The Great Canal and the China of the water. It can be read here

Last posts

The Horse God as One of the Most Popular Deities in China

The Horse God as One of the Most Popular Deities in China If a visitor goes to the Great Wall at Juyongguan, the section closest to Beijing and one of the most historically significant, and takes the time to explore the complex of structures carefully—a...

Geckos and the “Mark of Chastity” in Imperial China: History, Symbolism, and Cultural Context

Geckos and the “Mark of Chastity” in Imperial China: History, Symbolism, and Cultural Context Across the long span of imperial Chinese history, the gecko occupied a surprisingly prominent place in discussions of female chastity, bodily integrity, and the regulation of...

Why It Is Necessary to Study Suicide in Chinese Culture

Why It Is Necessary to Study Suicide in Chinese Culture While drafting new chapters for my Brief History of China, cases of suicide kept appearing in the most diverse circumstances. Ministers and wives who allowed themselves to be buried alive to accompany kings to...

The true origin of the Great Wall

The true origin of the Great wall, as seen in Nicola Di Cosmo (The Origins of the Great Wall. Silk Road Journal. 1993). Generally speaking, the political discourse about foreigners in pre-imperial China tends to justify expansion and conquest, which is exactly what...

Parnashavari: The Tibetan Goddess of Medicine

Parnashavari: The Tibetan Goddess of Medicine Within the complex symbolism of Tibetan deities and protectors, I like to look for distinctive details that allow us to identify a figure the moment we see them in a temple. One of the goddesses who makes this task...

The Smallpox Goddess (Doushen)

The Smallpox Goddess (Doushen) The Smallpox Goddess (Doushen 痘神) is part of a group of goddesses whose primary role was the protection of children. In the final years of the imperial era, they operated under the authority of Bixia Yuanjun, the daughter of the Emperor...