The Discipline Paintings in Tibetan Temples

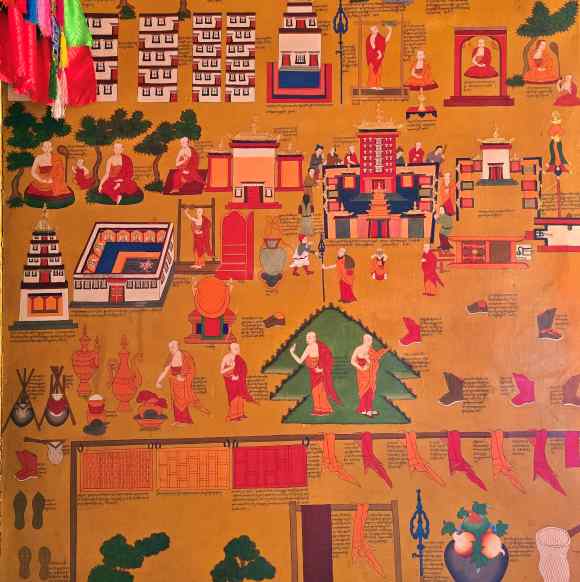

Among the paintings of deities, protectors, and other philosophical themes that usually decorate the entrance of a Tibetan Buddhist temple, some temples feature a very different kind of imagery. These are known as the “Keys of Discipline” or “Vinaya Keys.” They depict textiles, monastic robes, shoes, alms bowls, buildings, and, more generally, material objects rendered with the detachment of a commercial catalogue. In fact, they provide a graphic representation of the rules that govern monastic conduct.

These rules are clearly defined in a specific corpus of scriptures known as the Vinaya Piṭaka, which forms part of the Buddhist canon and must be memorized by all monks. It includes compulsory disciplinary regulations, internal judicial procedures, rituals of confession and expiation, and rules concerning dress, food, sexuality, property, and hierarchy. Its core text, the Prātimokṣa, contains 227 rules for monks and 311 for nuns, and is recited publicly every two weeks.

The Function of These Paintings

The purpose of these paintings is to show permitted actions, indicate prohibited ones, teach the correct use of objects, gestures, and spaces, and constantly remind monks of the ideal of proper bodily conduct. They can be grouped into the following categories:

- Rules on Movement and Bodily Posture

Figures of monks walking, standing, or sitting illustrate the correct way to move. One should not walk in a worldly manner, sway the body, gesture excessively, run, or move with unnecessary haste. Movement should be calm, with the gaze lowered, avoiding looking at women, markets, or public entertainments.

Proper sitting is also prescribed: one should not recline, cross the legs like a layperson, or adopt “decorative” or theatrical postures. - Rules on the Use and Placement of the Robe

The lower register, showing robes hung, folded, or laid out, is particularly explicit. Robes should never be placed directly on the ground. They must be dried in appropriate places, folded correctly, and worn properly. The monastic robe legally defines the monk, which is why these rules are so detailed. Another section regulates the type of footwear to be worn in different circumstances. - Rules Concerning Permitted Objects

These refer to the bowls, staffs, and utensils depicted. A monk is required to own only a single alms bowl, which must not be made of precious materials or be decorated, but rather simple and functional. The paintings also show the proper teapots used to serve tea to monks during prayers, and the cups from which it should be drunk. - Rules on Alms-Gathering and Religious Practice

These scenes indicate that alms should be requested in silence, without choosing specific houses or insisting on donations. Other figures are shown circumambulating a sacred building, while others meditate beneath a tree, illustrating the correct postures for these practices. - Rules on Architecture and Spatial Organization

Particularly striking are the rules concerning architecture and space. They define the ideal separation between monastic and lay areas, as well as the proper forms of monasteries, cloisters, altars, and stupas, clearly delineating each ritual space. - Rules on Hierarchy and Communal Conduct

Some paintings depict different monks and indicate their order of precedence, showing the correct way to approach a superior and emphasizing that one should never sit in a higher position than a senior monk.

As can be seen in the images, each of these aspects is accompanied by a specific explanation written in Tibetan next to the corresponding illustration.

In many monasteries, these paintings are located on the right-hand side of the entrance, while on the left are the Wheels of Life, which convey some of the most profound philosophical teachings of Buddhism. In this way, the two messages complement each other: correct conduct in every moment is presented as the necessary first step toward any spiritual ascent.

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China).

Last posts

Violence and cannibalism in the Five Dynasties

l l Violence and cannibalism in the Five Dynasties When one begins to know the history of China, one concentrates its readings on its brilliant moments, on those great dynasties that expanded the territory, recreated surprising cultural forms and became the greatest...

DRAMATIC ART IN CHINA AT THE END OF THE DYNASTIC REGIME

oyaaDuring a break in my studies, the afternoon of Christmas Eve I was looking through a cabinet in which I have some somewhat old books bought on various occasions at flea markets in Beijing and Shanghai. After running into Lewis Morgan's "Ancient Society" and taking...

The value of the Taotejing, the sacred book of the Taoists

In Peter Goullart The Monastery of the Jade Mountain. Unlike the Bible and the Koran. the Taoteking does not refer to the historical processes which led men, or rather a particular tribe among men, to the idea of One God. Neither does it describe in detail how this...

The path to Nirvana in the Kunming Dharani Pillar

The path to Nirvana in the Kunming Dharani Pillar The main courtyard of the Kunming Municipal Museum houses one of the most original art-works from the time of the Dali Kingdom (937-1253 CE) in Yunnan. It is called the Dharani Pillar of the Dizang Temple. It is a...

Legends of the Mother Goddess: Intro

From Leyendas de la Diosa Madre. Pedro Ceinos Arcones. Miraguano, 2007. Anyone who approaches the literature of the minorities of Southern China will discover numerous works where the leading role is played by a female goddess or deity. Whether dedicated to the...

Buddha as a true man: a different tale

In the fourth chapter of India in the Chinese Imagination: Myth, Religion, and Thought (edited by John Kieschnick and Meir Shahar, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014), Nobuyoshi Yamabe contributes an article (Indian Myth Transformed in a Chinese Apocryphal Text:...