Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art

In fact, only a few moments are repeated very frequently in Tibetan paintings. In some versions there are eight—an auspicious number for Tibetans, corresponding to the Noble Eightfold Path and the eight directions—and in others there are twelve, which may relate to the twelve months. Others—the so-called 108 scenes of his life—are reserved for more specialized paintings, such as the one that surrounds the hall of the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa. While the first type of paintings are easy to recognize because of their distinctive elements, the latter—using iconographic references to specific episodes of his public life—offer very interesting depictions of buildings, vehicles, and figures as they were used (or imagined) at the time they were painted. They are small encyclopedias of Tibetan historical life. Below are the most popular scenes.

- The Mother’s Dream (Mahāmāyā) with the White Elephant. The future mother of the Buddha, Mahāmāyā, dreams of a white elephant entering her navel. In thangkas she appears seated or standing, often amid clouds, while a white elephant (sometimes with a long trunk and broad ears) rises above her. The dream foretells the birth of an enlightened being.

- Birth at Lumbini. The infant Buddha emerges from his mother’s womb, sometimes floating on a cloud or on a flower-adorned couch. Mahāmāyā is shown holding the child, sometimes with a halo of light. In other versions the child already stands, pointing a finger toward the sky.

- The “Four Signs” (Four Visions). Siddhārtha sees an old man, a sick person, a corpse, and an ascetic. Each figure is usually isolated in a small panel around the prince. This marks the end of his life of pleasures and the beginning of his philosophical concerns.

- Departure from the Palace (Flight). The prince leaves the palace in the middle of the night riding his horse Kanthaka. In Tibetan art the horse is often surrounded by deities or celestial beings who hold its hooves to prevent noise from waking his wife and son, indicating supernatural assistance in his departure.

- Cutting the Hair. Siddhārtha cuts his own hair with a ceremonial sword or knife. The scene shows the prince kneeling, head uncovered, with his hair falling to the ground—symbolizing renunciation of the material world.

- Meditation under the Bodhi Tree. Siddhārtha sits in lotus posture beneath a large fig tree (the Bodhi). Devas (deities) and bodhisattvas may appear around him offering gifts or protection. Sometimes a “rain of flowers” symbolizes enlightenment.

- Enlightenment (Bodhi). The radiant Buddha, with a halo of fire or golden light, often surrounded by a mandala or the “Three Jewels.” Devas and bodhisattvas appear in reverent postures.

- First Sermon in the Deer Park. The Buddha teaches the Four Noble Truths to his first five disciples. Thangkas show deer, deciduous trees, and a multitude of devas listening attentively.

- The “Miracles of the Three Winds.” The Buddha levitates, produces fire beneath his feet and water above his head simultaneously. This scene demonstrates his mastery of the elements and compassion for the faithful.

- Parinirvāṇa (Death). The Buddha reclines on a couch or in a recumbent posture, surrounded by disciples and deities who mourn. The scene emphasizes liberation from saṃsāra (the cycle of rebirth) and entry into nirvāṇa.

All these scenes come from the Indian tradition, and different countries and Buddhist schools emphasized different moments. There are other famous scenes—some narrating the conversion of princes or murderers, specific teachings of the Buddha, or animals serving him during meditation or being calmed by his mere presence—but in my subjective recollection, those above are among the most popular in Tibet and the easiest for travelers to recognize.

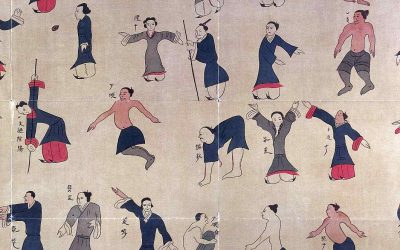

Image from the «108 scenes of Budha’s life» in Jokhang Temple, Lhasa.

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China).

Last posts

Laozi’s Mother is the goddess who created the world

Laozi’s Mother is the goddess who created the world In Taoist thought, great mysteries are not explained with definitive statements, but with paradoxical images, fragmentary myths, and bodily metaphors. One such mystery is the origin of the world—and for Taoism, that...

Does the Daodejing Contain the Oldest Creation Myth of China?

Does the Daodejing Contain the Oldest Creation Myth of China? An introductory article on Chinese mythology asserts (twice) that the myth of the creation of Huangdi (the Yellow Emperor) should be considered one of China's creation myths, following the model of...

The Wenzi Begins: Echoes from a Forgotten Taoist Voice

The Wenzi Begins: Echoes from a Forgotten Taoist Voice The Wenzi (文子) is an ancient Daoist text attributed to a disciple of Laozi. Although its authenticity has been debated throughout history, its content clearly reflects the Daoist worldview and its influence on the...

A Humble Proposal for Rethinking Historical Periodization: To Go Beyond Dynasties in Chinese History

A Humble Proposal for Rethinking Historical Periodization: To Go Beyond Dynasties in Chinese History Historical narratives are never neutral. The way we divide time reflects not only the facts we choose to remember, but also the frameworks we use to interpret them. In...

The Primitivist: The Taoist Philosopher of Simplicity

The Primitivist: The Taoist Philosopher of Simplicity The Taoist classic Zhuangzi is not the work of a single philosopherAnyone who takes a closer look at the foundational works of Taoism will quickly discover that the book known as Zhuangzi was not entirely written...

Zhang Yongzheng, the master of deluding reality

Zhang Yongzheng, the master of deluding reality Reality is an illusion, say Buddhist texts. And each of Zhang Yonggzheng's (Gansu, 1978) works plays with this concept to remind us again and again that there is no immutable reality but a fluid universe of forms that...