Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture

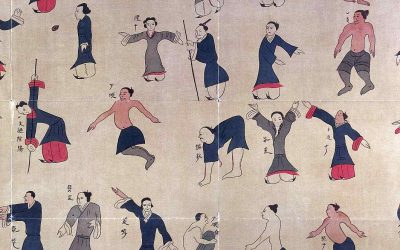

In early November 2022 my friend, the psychiatrist Luz González Sánchez, told me that she was preparing a lecture on suicide. On the 8th of that same month, during a quiet moment, I made a brief review of some of the types of suicide characteristic of China and sent it to her in case it might be of interest. In fact, I was in the final stages of writing my Secret History of China, and suicides appeared in it under the most diverse circumstances. Ministers and wives who voluntarily buried themselves to accompany kings into the other world; generals who took their own lives to avoid the humiliation of defeat; officials who did so to demonstrate the sincerity of their political ideas; Buddhist monks who cremated themselves as a supreme sacrifice while freeing themselves from the body that prevented them from reaching nirvana; women who committed suicide for fear of being raped during military campaigns; widows who ended their lives rather than remarry; and desperate citizens who did so after being designated political enemies during the violence unleashed following the establishment of the communist regime in the twentieth century. Most of these stories reflected traditional Chinese culture and showed that the motives that led people to take their own lives, their social consideration, the setting in which they did so, and even the means employed were also characteristic of this country.

There is no single book devoted to the culture of suicide in China

To my surprise, when curiosity led me to continue researching, I found no work that treated the subject in all its complexity[1]. Only a handful of books and academic studies have been devoted to the suicides of widows during the last dynasty and to those of Buddhist monks in medieval China, but none that describe and analyze suicide across the broad spectrum of Chinese history and culture. There are studies that highlight the importance of suicide in Chinese religion, history and culture, that explore and analyze the meaning of life and death for the inhabitants of this country in different historical periods and their consideration under different philosophical and religious systems, but none that incorporate all this information into a single book. J. J. Matignon (1936:61), who devotes much of his book to suicide, already said more than one hundred years ago: “A considerable volume could be written on suicide in China, since there is probably no country where this crime is more frequent. It is found in all classes and at all ages[2].”

The study of suicide offers a different perspective on Chinese culture.

Materials related to the study of suicide also provide alternative views of some concepts of Chinese thought or emphasize details generally neglected. Thanks to them we gain more precise ideas about loyalty to the sovereign or to the husband, sacrifices to request rain, violent death as a process of deification, the drama of gender violence, Taoist techniques of self-destruction, and Buddhist practices of self-immolation. Above all, they illuminate the atmosphere that led millions of people to sacrifice their lives for their ideas, for the good of the people, to leave a good name behind, or to avoid suffering.

The study of suicide in China is a complex matter, since it covers almost 4,000 years and very diverse situations, but it is also a fascinating process because it offers the researcher (and the reader) new and suggestive interpretations of history and society, new angles from which to assess and understand religion, and new data—often overlooked—that open new windows onto the understanding of the lives of those who shaped history. In reality, each facet of suicide raises more questions than answers, opening new fields for the study of Chinese culture. For this reason, the fundamental aim of this book has been to place the historical facts related to suicide within the religious and cultural frameworks that help to explain them, providing the reader with information to understand why people took their own lives in different historical and social contexts. But books have a life of their own and sometimes take their own path. This is one of those cases, and, unable to deny the evidence presented by my own work, it became necessary to explain how the Chinese conception of suicide was one of the decisive factors in the fall of the Qing dynasty and, with it, of the imperial regime.

Both the historian and the specialist in religion or society will discover, through the lens of suicide, new perspectives from which to observe their objects of study—perspectives that facilitate the understanding of archaeology, art, literature, and ritual life, since all these fields have been shaped by suicides. Scholars of Chinese religions already know that violent death, in war or by suicide, was the central fact in the creation of dangerous spirits or ghosts, which—unlike those who die within the family and become protective ancestors—wander the world and can cause disasters to humans. The struggle against and protection from them is the essence of religious activity in China.

There is but one truly serious philosophical problem: suicide.

The instinct for self-preservation, one of the strongest in human beings, surrounds everything related to the loss of life with an aura of mystery. Not without reason did Albert Camus state in his famous work The Myth of Sisyphus (1985:1): “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem: suicide.” And although this claim can be debated, the importance of the issue is undeniable. The study of suicide allows us to understand conceptions of life and death in different cultures, the role of individuals in society, the philosophical and moral ideas that shape life, and the various ways in which people attempt to fit their own existence into those structures. The study of suicide thus allows reflection on the great questions of philosophy: the meaning of life, its relationship with the always mysterious forces of an beyond, and with the much closer family and social community. For this reason, the study of suicide is a basic tool for understanding the human being, and the variations presented in this work are examples of the original answers that cultures have given to specific problems when approached from different philosophical or religious paradigms.

The study of suicide is, at the same time, the study of death—the most important fact in people’s lives and the one that conditions their existence more than any other. By showing situations that were considered more important than life itself, this book reveals original cultural and religious processes, regarded as exotic by a society that, in theory, places the value of life above everything else[3].

We will follow Durkheim’s definition.

Without entering into lengthy theoretical discussions, in this work we follow the definition of suicide formulated by the famous French sociologist Émile Durkheim (2005: xlii): “The term suicide is applied to all cases of death resulting directly or indirectly from a positive or negative act of the victim himself, which he knows will produce this result.”

In his work, Durkheim classified suicide into three categories: egoistic suicide, resulting from the lack of integration of an individual into society or the family; altruistic suicide, which occurs when a person takes their life out of religious or political loyalty, sometimes driven by a sense of duty or mystical enthusiasm; and anomic suicide, which also results from lack of integration and produces irritation or aversion toward life in general or toward groups or individuals in particular (Thomas 2012: 32; Durkheim 2005: 257).

Durkheim (2005: xlv) also pointed out that suicide is a contagious phenomenon, since people inclined to it are easily affected by suggestion, and that each society evaluates it differently at each historical moment. This is probably why its conception in traditional Chinese culture is so different from that of classical antiquity or that of contemporary society.

Nowadays the suicide is a grave problem

Today suicide occupies a central place in society. According to the World Health Organization, about 800,000 people take their own lives worldwide every year—twice the number of homicide victims. For every adult who dies by suicide, it is estimated that twenty others have attempted it, and each suicide intimately affects at least six other people. According to this same organization, suicide is the second leading cause of death among young people aged 15 to 29, behind only traffic accidents (Trujillo 2021). In Spain, almost 4,000 people died by suicide in 2024, and it is now the leading cause of death by external injuries, and among those under 30 the leading cause of death in absolute numbers. It is a major social problem and a terrible source of suffering for affected families.

In these times of cultural mixing and globalization, with cities in which people from all five continents live together, it is more necessary than ever to make known the special characteristics of Chinese suicide. Broadening the vision of this phenomenon will help to better understand its consideration among the Chinese population and in other cultures, its relationship with economic, political, and social changes, as well as the historical and cultural forces that led certain people in the past to end their lives.

[1] As books entirely dedicated to this subject, the following are essential: Janet M. Theiss, Disgraceful Matters: The Politics of Chastity in Eighteenth-Century China (University of California Press, 2004); James A. Benn, Burning for Buddha: Self-Immolation in Chinese Buddhism (University of Hawai‘i Press, Honolulu, 2007); and Wu Fei, Suicide and Justice: A Chinese Perspective (Routledge, 2010). The latter addresses contemporary suicides in rural China. Also a milestone in modern research was the special issue of Nan-nü on this subject coordinated by Paul Ropp in 2001.

[2] Although he himself cites E. Vicente, who said: “Suicide is a greater scourge in Japan than in China; people kill themselves at any age, for any reason and by any means.”

[3] At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Western society places the value of the individual’s life above everything else—but only if that individual belongs to society, or to the groups that dominate it, and only if that death is clearly linked to a cause. For this reason, attention is focused on processes that keep a person’s life in suspense, while hundreds or thousands of deaths far from the borders are ignored (or even caused). The anonymous dead that scientists predict will occur in the future as a consequence of policies adopted today—ranging from global warming and urban pollution to the use of agrochemicals and heavy metals in food—also do not count because of their anonymity, since although the number of deaths may be precisely quantified, it is not possible to specify, with names and surnames, who those victims will be.

Link to buy the book.

La cultura del suicidio en China y la caída del régimen imperial

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China).

Last posts

Laozi’s Mother is the goddess who created the world

Laozi’s Mother is the goddess who created the world In Taoist thought, great mysteries are not explained with definitive statements, but with paradoxical images, fragmentary myths, and bodily metaphors. One such mystery is the origin of the world—and for Taoism, that...

Does the Daodejing Contain the Oldest Creation Myth of China?

Does the Daodejing Contain the Oldest Creation Myth of China? An introductory article on Chinese mythology asserts (twice) that the myth of the creation of Huangdi (the Yellow Emperor) should be considered one of China's creation myths, following the model of...

The Wenzi Begins: Echoes from a Forgotten Taoist Voice

The Wenzi Begins: Echoes from a Forgotten Taoist Voice The Wenzi (文子) is an ancient Daoist text attributed to a disciple of Laozi. Although its authenticity has been debated throughout history, its content clearly reflects the Daoist worldview and its influence on the...

A Humble Proposal for Rethinking Historical Periodization: To Go Beyond Dynasties in Chinese History

A Humble Proposal for Rethinking Historical Periodization: To Go Beyond Dynasties in Chinese History Historical narratives are never neutral. The way we divide time reflects not only the facts we choose to remember, but also the frameworks we use to interpret them. In...

The Primitivist: The Taoist Philosopher of Simplicity

The Primitivist: The Taoist Philosopher of Simplicity The Taoist classic Zhuangzi is not the work of a single philosopherAnyone who takes a closer look at the foundational works of Taoism will quickly discover that the book known as Zhuangzi was not entirely written...

Zhang Yongzheng, the master of deluding reality

Zhang Yongzheng, the master of deluding reality Reality is an illusion, say Buddhist texts. And each of Zhang Yonggzheng's (Gansu, 1978) works plays with this concept to remind us again and again that there is no immutable reality but a fluid universe of forms that...