The true origin of the Great wall, as seen in Nicola Di Cosmo (The Origins of the Great Wall. Silk Road Journal. 1993).

- Generally speaking, the political discourse about foreigners in pre-imperial China tends to justify expansion and conquest, which is exactly what happened.

-Especially in the Warring States Period… general trend was towards the creation of larger and stronger states, which expanded not only by swallowing up other Chinese states but also by expanding into external areas.

– archaeological but also textual evidence suggest a historical context, on the eve of the building of the very first ‘great wall,’ in which the northern frontier zone appears to have been increasingly valuable, in economic and strategic terms, to northern Chinese states. 16. all theories converge to agree that the ‘great wall’ was built as a response to nomadic aggression.

-Surprisingly, there is no textual evidence that allows us to establish a direct cause-effect relationship between nomadic attacks and the building of the walls. The evidence shows, on the contrary, that the building of walls does not follow nomads’ raids, but rather precedes them. If a linkage can be established in terms of mere chronological sequence, the construction of the walls should be regarded as the cause, not as the effect, of nomadic incursions.

– Secondly, archaeological evidence does not support the contention that the walls were protecting a sedentary population, even less that they were protecting a ‘Chinese’ sedentary population. In fact, the early walls did not mark an ecological boundary between steppe and sown, nor did they mark a boundary between a culturally Sinitic zone and an alien ‘barbarian’ region. For the most part, they were entirely within areas culturally and politically alien to China.

- Explicit mention of wall building activity by the northern states is found in the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji), authored by Sima Qian around the turn of the second century BCE, that is, over two hundred years after the first northern walls were built, and after about a century of wars between the nomadic empire of the Xiongnu and China. Sima Qian inscribed such a long and bloody confrontation in a historical pattern according to which China (variously indicated as Hua, Hsia, Zhongyuan, Zhongguo, or even ‘the land of caps and sashes’) and the nomads constituted two antithetic poles that had been at odds ever since the dawn of Chinese history

- does the historical evidence show a connection between nomadic threats and wall-building? As for the state of Qin, the record says that its king Zhaoxiang (306-251 BCE) began to build walls on the north-western border after a military campaign into that territory, which was inhabited by a non-Chinese people called the Yiqu Rong. The state of Yan was located in the north-east.

During the reign of King Zhao (311-279 BCE), a general who had served as a hostage among the nomads made a surprise attack against the Eastern Hu. He defeated them, and forced them to retreat ‘a thousand miles.’ Yan then ‘built “long walls”’ and established commanderies ‘in order to resist the nomads.’

- The third northern state, Zhao, also had conflicts with steppe nomads. The Shiji tells us that King Wuling ‘in the north attacked the Lin Hu and the Loufan [both of them are generally understood to be nomadic peoples – NDiC]; built long walls, and made a barrier [stretching] from Dai along the foot of the Yin Mountains to Gaoque.’ Thus, Zhao created an advanced line of fortification, deep into today’s Inner Mongolia, encircling the Ordos steppe, then inhabited by pastoral nomads… The building of fortifications proceeded hand in hand with the acquisition of new territory, the transfer of troops to this region, and the establishment of new administrative units. The states of Qin, Zhao and Yan needed to protect themselves from the nomads only after they had taken large portions of territory from them.

– the Chinese presence here at this early time was limited only to sites connected with the wall fortifications themselves, showing that military colonies and troops were stationed in an otherwise ‘barbarian’ cultural environment. For sure the walls were not built between Chinese and nomads, but ran, from a Chinese viewpoint, through a remote territory inhabited by foreign peoples.

19. the states of Yan, Zhao, and Qin. They developed the system of long lines of fortifications to expand into the lands of nomadic or semi-nomadic peoples, and fence them off. Soldiers defended this territory against nomadic peoples possibly expelled from their pastures. This military push created a pressure on nomads that in turn led to a pattern of hostilities. The walls, in other words, were part and parcel with an overall expansionist strategy by Chinese northern states meant to support and protect their political and economic penetration into areas thus far alien to the Chinese world.

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China). In my travels, I have specialized in Yunnan, Tibet, the Silk Road, and other lesser-known places. Feel free to write to me if you’re planning a trip to China. The agency I collaborate with offers excellent service at an unbeatable price. You’ll find my email below.

Last posts

The dog in China’s ancient tombs

Pedro Ceinos Arcones. La Magia del perro en China y el mundo. Dancing Dragons Books. 2019. (Excerpts from the book) The dog in China’s ancient tombs In China, dogs buried with their owners have been discovered in archaeological sites belonging to the most important...

Some philosophical schools in Buddha’s times

Peter Harvey. Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. Cambridge University Press. 2013. (Excerpts from the book. Page 11 and ff.) In its origin, Buddhism was a Samana-movement. Samanas were wandering ‘renunciant’ thinkers who were somewhat akin to the early Greek...

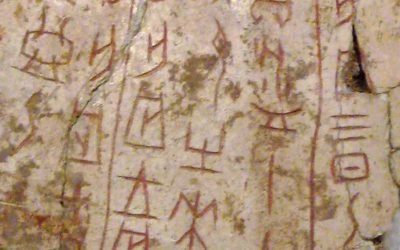

The origin of Chinese characters

The origin of Chinese characters in John C. Didier, “In and Outside the Square,” Sino-Platonic Papers, 192, vol. 1 (September, 2009) The technology of writing appears suddenly and morphologically fully developed on Shang oracle bones and, later, bronzes at about the...

The sacred Taishan mountain

Taishan Mountain, life and death in Chinese culture, according to the work of Edouard Chavannes Mountains are, in China, divinities. They are considered as nature powers who act in a conscious way and who can, therefore, be made favourable by sacrifices and touched...

A Taoist exorcism séance

'My friend is going to conclude an exorcism service this morning and, if you are really so interested, he hopes you can come and witness it.' He paused uncertainly. 'But I must warn 86 you that it is not a pretty sight. Really it is most unpleasant, disgusting and...

Chinese superstitions before the birth

To have five sons, rich, vigorous, literate and who become mandarins: this is the ideal of any Chinese family. From this matrix idea emerged the various types of popular images that are displayed in all households: Wu Zi Deng Ke (五子登科), Have five official children!...