The Lost Mythology of Ancient China

Reconstructing the mythology of ancient China is a painstaking task that tries to characterize some legendary figures and situations based only on the few sentences about them found in later works by philosophers and historians. The Classic of Mountains and Seas (Shanhaijing) helps to fill in some gaps, but its cryptic descriptions make it useful mainly for a small number of specialists.

A Lost Book

Much more useful is the Shiben, often translated as the Book of Origins, an ancient Chinese historical and genealogical text dating back approximately to the Warring States period (5th–3rd centuries BCE). The only problem is that the last known copy was lost during the Song dynasty, around 1,000 years ago. What would have been an irreparable loss in another culture has been partially recovered, thanks to China’s scholarly tradition. Over the past centuries, several scholars have attempted to reconstruct it based on references made in other texts that quote or cite it.

Contents of the Shiben

The Shiben is essential for understanding early Chinese history and especially how the ancient Chinese viewed their mythical and cultural origins — including royal genealogies, the beginnings of institutions, and legendary inventions. Among its main sections were the genealogies of kings and royal families, the origins of important feudal states and geographical places, and chronological lists of rulers with approximate dates or time periods.

It integrated legends and events that may have occurred in the distant past into a coherent narrative about the development of Chinese civilization. These reconstructions make the Shiben a key source for studying the historical and mythological worldview of ancient China.

Inventions from the Dawn of China

One of its most fascinating sections deals with the origins of professions, inventions, and techniques, attributing various aspects of cultural progress to their respective mythical inventors. Regardless of whether these claims hold historical accuracy, they are essential knowledge for anyone approaching Chinese culture. For example:

– Cang Jie, a minister of the Yellow Emperor, created Chinese characters by observing the tracks left by birds and animals. Legend says that when he finished, wheat rained down from the sky and spirits wept, because knowledge had entered the world — bringing both power and danger.

– Meng Tian, ignoring chronological consistency, was a general of the Qin dynasty who is credited with perfecting the Chinese brush and the use of ink made from vegetable carbon.

– Shen Nong, or the «Divine Farmer», taught humanity to cultivate grains, use plows, and identify medicinal plants. He is considered the father of agriculture and traditional Chinese medicine.

– Shaohao was the one who began domesticating animals for fieldwork and human service.

– You Chao Shi, meaning “He of the Nest”, had the idea of building elevated houses to protect people from wild animals and natural elements — a crucial step toward a sedentary lifestyle.

– Leizu, wife of the Yellow Emperor, is credited with discovering sericulture after observing silkworms making cocoons on mulberry leaves.

– Fu Xi, among other inventions, is attributed with creating fishing nets and the system of trigrams that later evolved into the I Ching (Yijing).

– Ling Lun, a musician of the Yellow Emperor, is said to have created the first Chinese musical scales based on bird songs.

– Gao Yao, a justice minister under Emperors Yao and Shun, laid the foundations of Chinese penal law and used a mythical unicorn (xiezhi) to detect lies and resolve disputes.

– Xi Zhong is credited with inventing wheeled carts — a major improvement in land transportation.

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China). In my travels, I have specialized in Yunnan, Tibet, the Silk Road, and other lesser-known places. Feel free to write to me if you’re planning a trip to China. The agency I collaborate with offers excellent service at an unbeatable price. You’ll find my email below.

Last posts

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven Those who know China—even if only through a brief trip—and who have visited the Temple of Heaven in Beijing will surely have been fascinated by the sober beauty of its buildings. Yet, whether on a crowded day or during a...

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art In fact, only a few moments are repeated very frequently in Tibetan paintings. In some versions there are eight—an auspicious number for Tibetans, corresponding to the Noble Eightfold Path and the eight...

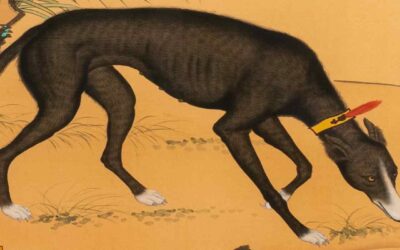

The Dog as Psychopomp in China

The Dog as Psychopomp in China One of the oldest human beliefs was that after death there existed an immaterial part of the person—later called the soul or spirit—that did not disappear with the body. Its origin may lie in the “presence” of the dead in dreams,...

An ambitious project to rewrite history

An ambitious project to rewrite history. It is what we see in Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene, The Nomadic Leviathan. A Critique of the Sinocentric Paradigm. Brill. Leiden. 2023. Now free to download in the publisher’s webpage. This book is a critique of a theoretical paradigm...

Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture

Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture In early November 2022 my friend, the psychiatrist Luz González Sánchez, told me that she was preparing a lecture on suicide. On the 8th of that same month, during a quiet moment, I made a brief...

The Tibetan Deity with a Horse Face

The Tibetan Deity with a Horse Face During my most recent journey to Tibet, someone pointed out to me in a temple a deity who bore a small horse upon his head. I knew that this protector is called Hayagriva, and that he is sometimes referred to as “Horse-Headed” or...