The Largest Collection of Paintings from ancient China

No one doubts that pictorial art has existed in China since time immemorial. In fact, some painted pottery vessels, several thousand years old, continue to intrigue archaeologists who try to unravel their ultimate meaning. There are also sources that confirm that the palaces of the Warring States period were decorated with paintings, and during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) it is well documented that walls were adorned for educational purposes, with images of sages, heroes, and moral scenes intended to inspire both the court and society.

The immense destruction caused in the centuries prior to our era makes one think that this magnificent art form has been lost forever.

Where are China’s oldest paintings?

Forever? Perhaps not entirely. Although the wall paintings of palaces and temples have not survived to our day, what we do have—thanks to traditional funerary practices—are hundreds of square meters of mural paintings preserved inside tombs excavated in stone or brick.

So far, more than 70 tombs with mural paintings from the Han dynasty have been discovered, mainly in regions such as Henan, Shandong, Shaanxi, Jiangsu, and Sichuan. Each has its own unique characteristics, but they also share a common thematic and stylistic repertoire that reveals much about how they conceived death, the afterlife, and the role of power even beyond earthly existence.

Although each tomb may contain only a few square meters of paintings, the combined total of all these works exceeds thousands of square meters, making them, collectively, the largest known pictorial collection of ancient China. The geographical and cultural conditions of each region also allow us to discover important aspects of the culture of the time and the style of its great artists.

Transformations in Funerary Culture

The mural paintings of Han tombs appear at a crucial moment of transformation in Chinese funerary culture. Until then, it was believed that the souls of the deceased simply descended to the Yellow Springs, an undefined underworld where they disappeared without return.

But during the Han dynasty, this vision changed radically. New beliefs emerged suggesting that the soul could travel to other dimensions and would, in some way, live again on another plane of existence. This change meant that tombs ceased to be simple burials and became spaces prepared for the afterlife: decorated, equipped places full of images that would help the spirit recognize its identity and find its way in the beyond.

A Treasure to Understand the Past

Beyond their artistic value, the mural paintings are authentic historical documents. Thanks to them, we can still learn about the clothes and hairstyles of the nobility, what musical instruments were used, what domestic life was like among noble families, or the hunting scenes, ceremonies, and banquets that marked the routine of the powerful.

This is not just art, but a direct testimony of how the Chinese lived, dreamed, and died two thousand years ago.

Recurring Themes and Deep Symbolism

Although each tomb is unique, many share a common iconographic structure, which includes:

- The Four Celestial Animals: the green dragon, the white tiger, the red bird, and the black tortoise—guardians of the cardinal points and guides of the soul on its journey.

- Funerary chariots and processions: reflecting the status of the deceased and their transition to the higher world.

- Human figures: servants, musicians, warriors, magistrates, and even the deceased themselves.

- Scenes of daily life: banquets, hunts, rituals, offerings.

All of this is organized following a carefully designed spatial and symbolic logic to accompany the deceased on their spiritual journey.

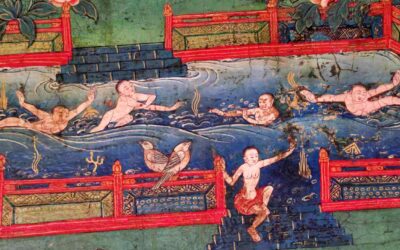

Technique and Materials: A Mature Pictorial Tradition

The mural paintings of the Han tombs used quite advanced techniques for their time. The preparation of the surfaces involved applying a layer of plaster or clay over the bricks or stone walls to create a uniform base. Mineral pigments were used, such as cinnabar red, carbon black, malachite green, lead white, and orpiment yellow. First, the silhouette was drawn with black ink or dark pigment, and then the areas were filled with flat colors, without shadows or complex perspectives, but with great expressiveness. The result is a work that, although flat, conveys movement, solemnity, and color, achieving an impressive effect even today.

A Heritage in Danger

Unfortunately, many of these tombs are at risk. Some were looted before being studied. Others suffered irreversible damage after their discovery due to humidity, exposure to air, or even poorly managed tourism. Today, it is estimated that more than 400 tombs with mural paintings have been discovered throughout China, but only a few are truly well preserved.

In response, Chinese archaeologists and museums have adopted various strategies: photographic documentation and 3D digitization, controlled extraction of fragments for museums, temporary closure of tombs to prevent deterioration, and virtual reproductions for the public.

A Jewel Among Many: The Jijiazhuang Tomb (Anping, Hebei)

Among the Han tombs with mural paintings, the tomb of Jijiazhuang, in Anping County, Hebei Province, stands out especially for its beauty and size. Discovered in 1971, this brick tomb contains over 200 square meters of paintings depicting various scenes. The most impressive is the imperial procession with chariots and guards. But there are also the mythological animals guarding the path, celestial figures guiding the soul of the deceased, and more.

The mural paintings of Han tombs are not just art; they are testimonies of a civilization that viewed death as a new beginning and sought to accompany their dead with all possible splendor. They are an essential part of the history of world art and deserve attention, study, and protection. Books like Complete Collection of Mural Paintings Discovered in China 《中国出土壁画全集》, with quite affordable digital versions, can satisfy the curiosity of those interested in the history of art.

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China). In my travels, I have specialized in Yunnan, Tibet, the Silk Road, and other lesser-known places. Feel free to write to me if you’re planning a trip to China. The agency I collaborate with offers excellent service at an unbeatable price. You’ll find my email below.

Last posts

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven Those who know China—even if only through a brief trip—and who have visited the Temple of Heaven in Beijing will surely have been fascinated by the sober beauty of its buildings. Yet, whether on a crowded day or during a...

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art In fact, only a few moments are repeated very frequently in Tibetan paintings. In some versions there are eight—an auspicious number for Tibetans, corresponding to the Noble Eightfold Path and the eight...

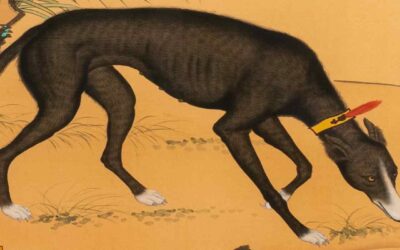

The Dog as Psychopomp in China

The Dog as Psychopomp in China One of the oldest human beliefs was that after death there existed an immaterial part of the person—later called the soul or spirit—that did not disappear with the body. Its origin may lie in the “presence” of the dead in dreams,...

An ambitious project to rewrite history

An ambitious project to rewrite history. It is what we see in Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene, The Nomadic Leviathan. A Critique of the Sinocentric Paradigm. Brill. Leiden. 2023. Now free to download in the publisher’s webpage. This book is a critique of a theoretical paradigm...

Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture

Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture In early November 2022 my friend, the psychiatrist Luz González Sánchez, told me that she was preparing a lecture on suicide. On the 8th of that same month, during a quiet moment, I made a brief...

The Tibetan Deity with a Horse Face

The Tibetan Deity with a Horse Face During my most recent journey to Tibet, someone pointed out to me in a temple a deity who bore a small horse upon his head. I knew that this protector is called Hayagriva, and that he is sometimes referred to as “Horse-Headed” or...