The Lahu Matriarchy: An Egalitarian Dyadic Society in China

From the book: Mothers, Queens, Goddesses, Shamans: Matriarchy in China (Miraguano, Madrid, 2011)

The egalitarian society of the Lahu drew academic attention with Du Shanshan’s study Chopsticks Only Work in Pairs, which reveals a world built upon the complementarity of male and female elements forming a dyad. This model “demonstrates both the existence of gender-equal societies and the possibility of achieving such conditions peacefully.”[1] If this is true among the Lahu, could it not also be the case for other peoples who share similar myths and traditions?

Du presents a society where gender equality is expressed in the couple, who run their household together with no preference for sons or daughters, and with no imposed rules about whether the newlyweds live with the husband’s or the wife’s family. In fact, most couples first reside with the wife’s parents, then the husband’s, before establishing their own household.

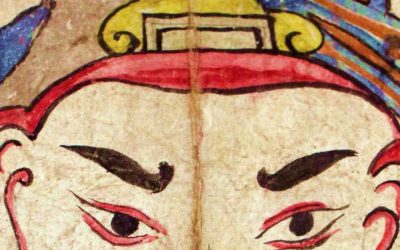

Their religion revolves around the deities XeulSha—a pair of inseparable twins, XeulYad and ShaYad—who encompass their mythology, culture, and way of life. When Buddhism arrived, they associated Buddha with XeulSha and always built two temples, in line with their dual cosmology. According to the Lahu, the first human pair emerged from a gourd, created by XeulSha. Other deities also appear in pairs, as do the ancestral couples honored in rituals.

The Lahu’s Dual Cosmology

New Year celebrations consist of two parts: a female component (the Great New Year) and a male one (the Little New Year). The world of the living and the world of the dead are complementary; every living family has its mirror image in the afterlife. A person’s death is believed to correspond to someone else’s birth in the realm of the dead. At funerals, people must attend in pairs, or else risk being trapped in the other world.

Union of the two halves does not imply opposition, but completeness. Marriage is the individual’s way of entering into society: to form part of a dyad is to become fully human. The wedding has two parts, held at the homes of the bride and groom, where maternal uncles give guidance to the newlyweds.

It is believed that both men and women can gestate children, although women give birth for practical reasons. During childbirth, the husband is actively involved, assisted by both sets of parents. He prepares the baby’s place, supports the woman as she squats, helps with delivery, massages to expel the placenta, and cuts the umbilical cord. Afterwards, he carries his wife to rest[2].

XeulSha: Female Creator of the World

Lahu scholars Xiao Gen, a married research team, emphasize the feminine nature of their society. For them, XeulSha or Eh Sha was originally an almighty goddess—similar to Nuwa in Chinese mythology—later masculinized as men gained dominance. In their myths, she created the first man and woman by imitating spiders, stretching a web across the sky. The man, lazy, made a small sky; the woman, diligent, made a vast earth. To make them fit, she wrinkled the earth, forming mountains and valleys.

Then came a couple born from a gourd, followed by nine more pairs that populated the world. The gourd, symbolizing the female womb, is still honored between the 15th and 17th of the 10th lunar month, when women dance around it to commemorate the creation of the people[3].

Xiao Gen found multiple matriarchal traits still alive: matrilocal residence, joint household leadership, equal ancestral worship, and women-led religious ceremonies. Elder women enjoy moral authority and are widely consulted. According to myth, there was a time of great prosperity under matriarchal clans led by a senior woman[4]. Some villages still preserve this structure—husbands move in with their wives, and the eldest daughter inherits the home.

When a child disobeys, the mother exposes her breasts and invokes Eh Sha, who will punish any child who rejects the one who nursed them[5].

A Unique Balance of Matriarchy and Patriarchy

While Xiao Gen emphasize the matriarchal aspects of Lahu society, they ultimately describe a dyadic system similar to that shown by Du. They argue that a unique social phenomenon emerged in Lahu culture—an equilibrium between matriarchy and patriarchy—resulting in a community organized along sex-based lines. One unit is headed by a matriarch and her female descendants, and another by the patriarch and his male descendants.

There is equality between spouses, who work together, marry freely, and make their own decisions with only parental approval. When the mother dies, her daughters inherit; when the father dies, his sons do. Each gender group owns the crops it cultivates. In religious rites, women and men both participate, although sometimes women lead socially and ritually. Women worship female ancestors, and men their male ancestors[6].

This elevated status of women is attributed to their vital role in both production and reproduction in ancient times. Hence, female figures are portrayed in myths as creators of humanity and providers of the staple grains. Their influence shapes Lahu religion, mythology, society, marriage, family, and everyday life[7].

Female Hunters and Warriors

Lahu women also participate in hunting and defense. Nayi, a legendary ancestor, was a huntress known for fairly sharing the catch. When enemies invaded, women defended their homes alongside the men[8]. Given the high status of women and possible migration routes from Qinghai province, some believe the Lahu established the matriarchal kingdoms of Supi and Tuomi—two legendary women’s realms during the Tang era[9]. However, linking modern societies with ancient political entities thousands of kilometers and centuries apart must be approached cautiously, as such claims may reflect the political agendas of minority elites more than rigorous historical analysis.

Anthropologist Anthony Walker also highlights this gender balance, noting that women actively participate in the economic, social, and family spheres. Girls often initiate relationships, and newlyweds frequently settle in the woman’s village. In his version of the Lahu creation myth, the supreme deity—whom he names Guisha—is androgynous, though especially feminine in stories about the origin of agriculture[10].

With the arrival of Buddhism, indigenous influence led to temples honoring a divine pair: Guanyin and Guisha. To maintain their traditional duality, Guisha may have been reinterpreted as male.

Matriarchal Longhouses

Huang Fang and Wen Jin recount that, up until the Chinese revolution, Yellow Lahu communities were organized around large matriarchal longhouses, inhabited by grandmothers, their daughters, and granddaughters. These houses, often elevated bamboo and wood structures, held 50 to 100 people, forming whole villages.

The senior woman of the house—usually the eldest—acted as leader. Upon her death, the role passed to her eldest daughter. Descent was traced through women, and land was held communally, farmed collectively, and enjoyed equally. The matriarch oversaw production, though she listened to everyone’s input. Grain was stored beside the house and guarded by one of the women.

Sexual freedom was the norm. In the evenings, young women visited neighboring villages, where they met young men. Together, they would climb the hills to sing, and some couples formed. During New Year, elders would escort youth to visit nearby communities where they were warmly welcomed. If a couple decided to marry, the girl’s family would formally request the boy’s hand at least three times, showing interest. The groom would move into the bride’s household, bringing only his blanket. Divorce was generally accepted, and children stayed with the mother, as members of her matriarchal clan[11].

A Fading Tradition

This egalitarian society has gradually faded under the influence of Chinese culture, surviving only in the most remote communities. Despite official rhetoric, local authorities do not acknowledge female leaders, engaging only with male political and religious heads. Even many researchers overlook the role of women in leading Lahu society[12].

[1] Du Shanshan. Chopstick only works in pairs. Columbia University Press. New York. 2002, p. 1

[2] Du Shanshan, 2002.

[3] Xiao Gen. The Lahus, love through reed -pipe wind and mouth string. Yunnan Education Publishing House. Kunming. 1995. Xiao Gen. Lahu zu nuxing chongbai guannian tanxi (Practical explration of the feminine cults among the Lahu). In «Yunnan Minzu Xueyuan wushi zhou nian jiao qing xueshu lun wen ji» Gathering of papers to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Yunnan Institute of Nationalities. Yunnan University Publishing House. Kunming. 2001. And Song Liying, 2007

[4] Xiao Gen, 1995, p. 4.

[5] Xiao Gen, 1995, p. 7.

[6] Xiao Gen, 1995, p. 6-7.

[7] Xiao Gen, 2001, p. 453

[8] Xiao Gen 1995, p. 9-10.

[9] Xiao Gen 1995, p. 8.

[10] Waker, Anthony (ed.). Mvuh Hpa Mi Hpa Creating Heaven, Creating Earth: An Epic Myth of the Lahu People in Yunnan. Silkworm Books. 1995.

[11] Huang Fang and Wen Jin. Nuren fengqing (Folklore of the Women). Sichuan Nationalities Press. Chengdu. 1988.

[12] Du 2002, p. 138.

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China). In my travels, I have specialized in Yunnan, Tibet, the Silk Road, and other lesser-known places. Feel free to write to me if you’re planning a trip to China. The agency I collaborate with offers excellent service at an unbeatable price. You’ll find my email below.

Last posts

A Giant Mandala in the Heart of Tibet

A Giant Mandala in the Heart of Tibet The Palkor of Gyantze is one of Tibet’s great marvels and a unique jewel of universal architecture and art. Its shape, scale, and iconography defy comparison with any other construction. Amidst some of the highest mountains of...

The Largest Collection of Paintings from ancient China

The Largest Collection of Paintings from ancient China No one doubts that pictorial art has existed in China since time immemorial. In fact, some painted pottery vessels, several thousand years old, continue to intrigue archaeologists who try to unravel their ultimate...

The Real Situation of Women in the Qing Dynasty

The Real Situation of Women in the Qing Dynasty Guo Songyi[1] has raised several important points about the situation of Chinese women during the Qing dynasty—points that could fundamentally reshape how both the public and academic researchers view this period. What...

Laozi’s Mother is the goddess who created the world

Laozi’s Mother is the goddess who created the world In Taoist thought, great mysteries are not explained with definitive statements, but with paradoxical images, fragmentary myths, and bodily metaphors. One such mystery is the origin of the world—and for Taoism, that...

A detective story among the Dai nationality

A detective story among the Dai nationality Among the rich folk literature of the Dai nationality, living in the south and western borders of Yunnan province, mainly in the Xishuangbanna and Dehong Autonomous Prefectures the tales of the tricksters[1] Aisu and Aixi...

Does the Daodejing Contain the Oldest Creation Myth of China?

Does the Daodejing Contain the Oldest Creation Myth of China? An introductory article on Chinese mythology asserts (twice) that the myth of the creation of Huangdi (the Yellow Emperor) should be considered one of China's creation myths, following the model of...