Pedro Ceinos Arcones. La Magia del perro en China y el mundo. Dancing Dragons Books. 2019.

(Excerpts from the book)

The dog in China’s ancient tombs

In China, dogs buried with their owners have been discovered in archaeological sites belonging to the most important cultures. One of the oldest is that of Jiahu, in Wuyang, some 9,000 years ago, where the eleven dogs buried in their homes and cemeteries already suggest complex symbolic systems and evidence of shamanistic rituals, characterized by the custom of burying dogs in tombs and foundations of houses. A ritual that will remain alive for thousands of years, having also been discovered in the Neolithic village of Bampo, inhabited some 6,000 years ago, as well as in later settlements of the historical epoch. This indicates that the dog was used as a watchdog and that this function had acquired a magical and spiritual dimension (Underhill 2013:224, Yuan 2008).

Dogs accompanying people were found in the funerary grounds of other settlements. In tombs that gradually become more sophisticated, especially the largest that are believed to have belonged to the ruling class were included symbols that mark the belief in a new life (red marks, the color of life), perhaps in another world similar to that of the living (burials with ritual objects and others of daily use) and a route that the soul must pass (with the help of the dog).

Other ancient remains suggest that the dog was the companion of man and that he was not bred as food. The analysis of certain isotopes in their bones shows that they ate basically the same food. On the bones of deer and other animals consumed by their flesh, no incisions made by dog’s teeth have been discovered, while there are marks of teeth of rats and other carnivores. That means that dogs were not fed on human waste, but their role in the family economy was valuable enough to feed them with care. In addition, the general pattern of canine skeletons, often whole and uncut in their bones, responds more to that of the humans than to the animals consumed by their meat, usually cut up to be handled more easily. Finally, the different sizes of dogs unearthed from this long period show that different breeds of dogs adapted to different tasks were already being selected in China (Wang 2011).

The dog as a funerary element reaches great exuberance during the Shang dynasty (XVI-XI BCE), when not only were the tombs of the most powerful were furnished with a surprising amount of bronze objects, some of magnificent craftsmanship, but the number of sacrificial victims, including human victims, increased tremendously. Amid the imperial ardor that gave rise to massive sacrifices of enemies in tombs and in the consecration of public buildings, the dog continued to represent a foremost meaning. Its presence accompanying its master on the journey to the afterlife is a constant in the tombs of the Shang dynasty. Even in relatively humble burials, it is surprising to find the presence of dogs as companions. We know it is not a guardian because it is not at the door, but next to the deceased, usually just below him, looking in the same direction, sometimes with its own coffin. It is the guide and traveling companion. It is the companion of the dead par excellence.

An assessment of the inscriptions on oracular bones, the first Chinese writing, widely used during this dynasty for divinatory purposes, shows that the dog was one of the sacrifices of choice for the deities of the winds. Possibly because of its luminal position at the boundary of the worlds, its sacrifice became common in rituals related to the deities of the directions and of the rains (Eno 2010). The sacrifice of dogs was also common in the founding of cities and public buildings, as well as to worship the deities of the earth, for they appear buried. During this dynasty, there were dog breeding centers, where specimens were selected for hunting and sacrifices. Hunting had a ritual and military character for the Shang. The royal hunting expeditions showed the sovereign in his double dominion of the natural and human world, as the lord of nature and owner of the lands inhabited by men. During the hunt, the king was accompanied by many dogs kept in charge of officers stationed near the hunting grounds.

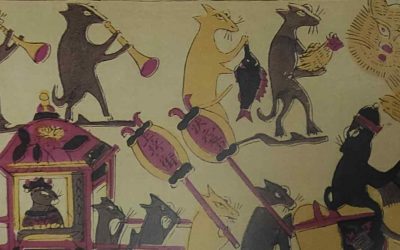

Image: China Cultural Relics

More posts on Chinese culture

Shadow – A Film by Zhang Yimou

Shadow - A Film by Zhang Yimou Zhang Yimou leads one of the most consistent and brilliant careers in the cinematography of China, and with The Shadow (Ying) he delights the viewer again with a beautiful and surprising story, based on a very original script, and that...

The horse in the Chinese horoscope

The horse in the Chinese horoscope The horse is one of the animals of later incorporation into Chinese culture. If, as some scholars say, the system of 12 animals in the Chinese horoscope originated in the peoples who lived in the north, in the steppes and deserts...

The rat in the Chinese horoscope

The rat in the Chinese horoscope The rat for the Chinese is an animal to which are associated some positive and some negative qualities, in fact it is considered capable of carrying out numerous enterprises, not in vain it was the first animal to be assigned a sign of...

An oriental interpretation of dreams

An oriental interpretation of dreams Last week, in a book about the Hani minority in the remote Jinping region, one of the authors devoted part of his article on divination to dream interpretation among the Hani. I translated it, added some comments and published it...

What does it mean to dream of a cow in China? We tell you here

What does it mean to dream of a cow in China? We tell you here In the last few days I have stumbled upon several documents dealing with dreams in China, and some with certain fragments explaining, in particular, the meaning of dreaming about a cow. One of the most...

The ox and the ritual plow in springtime

The ox and the ritual plow in springtime Throughout the imperial era, every year the beginning of agricultural work was celebrated by a solemn ceremony called the Plowing Festival. "The emperor himself would take a yellow plow attached to a yellow ox (yellow was the...

More posts on China ethnic groups

No se encontraron resultados

La página solicitada no pudo encontrarse. Trate de perfeccionar su búsqueda o utilice la navegación para localizar la entrada.