Pedro Ceinos Arcones. La Magia del perro en China y el mundo. Dancing Dragons Books. 2019.

(Excerpts from the book)

The dog in China’s ancient tombs

In China, dogs buried with their owners have been discovered in archaeological sites belonging to the most important cultures. One of the oldest is that of Jiahu, in Wuyang, some 9,000 years ago, where the eleven dogs buried in their homes and cemeteries already suggest complex symbolic systems and evidence of shamanistic rituals, characterized by the custom of burying dogs in tombs and foundations of houses. A ritual that will remain alive for thousands of years, having also been discovered in the Neolithic village of Bampo, inhabited some 6,000 years ago, as well as in later settlements of the historical epoch. This indicates that the dog was used as a watchdog and that this function had acquired a magical and spiritual dimension (Underhill 2013:224, Yuan 2008).

Dogs accompanying people were found in the funerary grounds of other settlements. In tombs that gradually become more sophisticated, especially the largest that are believed to have belonged to the ruling class were included symbols that mark the belief in a new life (red marks, the color of life), perhaps in another world similar to that of the living (burials with ritual objects and others of daily use) and a route that the soul must pass (with the help of the dog).

Other ancient remains suggest that the dog was the companion of man and that he was not bred as food. The analysis of certain isotopes in their bones shows that they ate basically the same food. On the bones of deer and other animals consumed by their flesh, no incisions made by dog’s teeth have been discovered, while there are marks of teeth of rats and other carnivores. That means that dogs were not fed on human waste, but their role in the family economy was valuable enough to feed them with care. In addition, the general pattern of canine skeletons, often whole and uncut in their bones, responds more to that of the humans than to the animals consumed by their meat, usually cut up to be handled more easily. Finally, the different sizes of dogs unearthed from this long period show that different breeds of dogs adapted to different tasks were already being selected in China (Wang 2011).

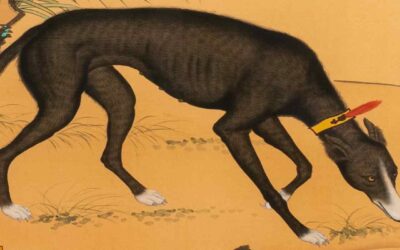

The dog as a funerary element reaches great exuberance during the Shang dynasty (XVI-XI BCE), when not only were the tombs of the most powerful were furnished with a surprising amount of bronze objects, some of magnificent craftsmanship, but the number of sacrificial victims, including human victims, increased tremendously. Amid the imperial ardor that gave rise to massive sacrifices of enemies in tombs and in the consecration of public buildings, the dog continued to represent a foremost meaning. Its presence accompanying its master on the journey to the afterlife is a constant in the tombs of the Shang dynasty. Even in relatively humble burials, it is surprising to find the presence of dogs as companions. We know it is not a guardian because it is not at the door, but next to the deceased, usually just below him, looking in the same direction, sometimes with its own coffin. It is the guide and traveling companion. It is the companion of the dead par excellence.

An assessment of the inscriptions on oracular bones, the first Chinese writing, widely used during this dynasty for divinatory purposes, shows that the dog was one of the sacrifices of choice for the deities of the winds. Possibly because of its luminal position at the boundary of the worlds, its sacrifice became common in rituals related to the deities of the directions and of the rains (Eno 2010). The sacrifice of dogs was also common in the founding of cities and public buildings, as well as to worship the deities of the earth, for they appear buried. During this dynasty, there were dog breeding centers, where specimens were selected for hunting and sacrifices. Hunting had a ritual and military character for the Shang. The royal hunting expeditions showed the sovereign in his double dominion of the natural and human world, as the lord of nature and owner of the lands inhabited by men. During the hunt, the king was accompanied by many dogs kept in charge of officers stationed near the hunting grounds.

Image: China Cultural Relics

More posts on Chinese culture

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven Those who know China—even if only through a brief trip—and who have visited the Temple of Heaven in Beijing will surely have been fascinated by the sober beauty of its buildings. Yet, whether on a crowded day or during a...

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art In fact, only a few moments are repeated very frequently in Tibetan paintings. In some versions there are eight—an auspicious number for Tibetans, corresponding to the Noble Eightfold Path and the eight...

The Dog as Psychopomp in China

The Dog as Psychopomp in China One of the oldest human beliefs was that after death there existed an immaterial part of the person—later called the soul or spirit—that did not disappear with the body. Its origin may lie in the “presence” of the dead in dreams,...

An ambitious project to rewrite history

An ambitious project to rewrite history. It is what we see in Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene, The Nomadic Leviathan. A Critique of the Sinocentric Paradigm. Brill. Leiden. 2023. Now free to download in the publisher’s webpage. This book is a critique of a theoretical paradigm...

Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture

Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture In early November 2022 my friend, the psychiatrist Luz González Sánchez, told me that she was preparing a lecture on suicide. On the 8th of that same month, during a quiet moment, I made a brief...

The Tibetan Deity with a Horse Face

The Tibetan Deity with a Horse Face During my most recent journey to Tibet, someone pointed out to me in a temple a deity who bore a small horse upon his head. I knew that this protector is called Hayagriva, and that he is sometimes referred to as “Horse-Headed” or...

More posts on China ethnic groups

The Bull that Shaped the World and Other Sacred Bovines among the Bulang Minority

The Bull that Shaped the World and Other Sacred Bovines among the Bulang Minority The Bulang people (布朗族), an Austroasiatic ethnic group primarily inhabiting Yunnan’s tea-growing highlands, revere the ox as a sacred being intertwined with creation, agriculture, and...

The Lahu Matriarchy: An Egalitarian Dyadic Society in China

The Lahu Matriarchy: An Egalitarian Dyadic Society in China From the book: Mothers, Queens, Goddesses, Shamans: Matriarchy in China (Miraguano, Madrid, 2011) The egalitarian society of the Lahu drew academic attention with Du Shanshan’s study Chopsticks Only Work in...

An Old Book on the Sani-Yi Minority

An Old Book on the Sani-Yi Minority One may wonder whether it makes any sense to read, in the first decades of the 21st century, a book written at the end of the 19th. Clearly, the person who has spent some of their time translating it, revising it, updating the old...

Sexual aspects of Gu venom

Gu illness resulted from a contamination by gu poison, which a recent analyst has characterized as “an alien evil spirit which entered [the] body and developed into worms or some similar animal that gnawed away at the intestines or genitalia.” This poison was thought...

Sunset in Dali

No Words Fuxing Rd from the South Gate. Dali, Yunnan.Corner in Fuxing Rd, Dali, Yunnan.Night market at the south of the South Gate. Dali. YunnanLast posts

The five secret temples of the lamas in Lijiang

The five secret temples of the lamas in Lijiang Religions of Lijiang Although the city of Lijiang is known primarily for the Dongba religion practiced by the traditional shamans of the Naxi, also called Dongba, who with their rituals administered the religious and...