The Dog as Psychopomp in China

One of the oldest human beliefs was that after death there existed an immaterial part of the person—later called the soul or spirit—that did not disappear with the body. Its origin may lie in the “presence” of the dead in dreams, sometimes in episodes that rival waking life in realism, and in certain spiritual experiences. As Lewis Spence noted in his seminal work on mythology, most simple cultures believe that these spirits move to another dimension of reality, generally imagined as a paradise located on hard-to-reach islands or mountains, or in subterranean or celestial regions. To reach it, the soul must usually undertake a complex journey, since its completion marks arrival in territories from which it can no longer return. The concept of a judgment on actions performed in life and the rewards or punishments inherent in heaven and hell is much more recent.

The Dog as Guide After Death

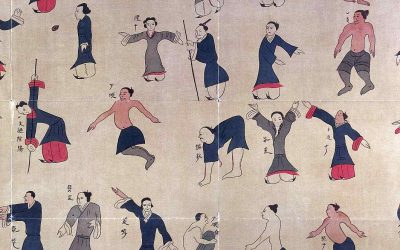

Once the belief arose that after death the soul undertook a painful journey and that a guide was necessary, the dog—accustomed to accompanying hunters on their expeditions—became the animal of choice. In addition, the dog has certain characteristics that would naturally have made it suitable for this role. It is familiar with the earth, which it digs and sniffs incessantly; it is accustomed to dealing with death, for in a world of frequent wars, in which the corpses of enemies were often left exposed, dogs were among the animals that fed on them. It is also familiar with the world of spirits, is able to see in the dark, and, thanks to its good sense of orientation, can act as a guide in unknown environments.

How Was the Other World Imagined?

That other world was imagined as similar to the earthly one, but with a fundamental incompatibility that makes communication between the two almost impossible, as described in an ancient myth of the Tuva of Mongolia:

“There was once a time when a hunter took shelter from a violent storm in a cave. Inside he found a world like ours, with people, cows, dogs, etc., but he caused problems in that world just as a ghost would in ours: he was invisible, only dogs could see his dog, he had to eat other people’s food, children fell ill when he touched them, and people tried to expel him by means of magic, as people do in this world.” (Tátar 1996: 270)

These qualities that made the dog the ideal animal to accompany the soul on its journeys after life were “visualized” during shamanic experiences. Ancient burials of dogs together with one or more persons seem to indicate that the dog was already being used as a guide for souls after death. After this identification of the dog with death and with the earth, it was also linked with death and the sky, likewise leading the soul of the dead to the celestial spheres—an initially happy adventure that would end with reunion with the ancestors in paradise, later transformed into the great tragedy of death.

Evolution of the Image of the Dog and Death

As concepts of the afterlife developed in more complex cultures, the dog remained a symbol of death, now acting as a psychopomp, as the first judge of souls at the gate of a paradise that it would allow only those who met certain moral requirements to enter, or posted at strategic points along the path of souls, marking the irreversibility of death and the impossibility of return. For the souls of the dead cannot come back; they must remain in their own world and no longer mingle with the living, except on certain festivals when the gates of the underworld are opened. In the end we even find the dog in seemingly disparate roles—attacking souls, causing death by its mere presence, or taking possession of the abandoned body—visualized in Tibetan near-death experiences. In these funerary settings dogs also appear in representations of the life imagined in the other world, accompanying their masters in the home or on hunting expeditions.

From the rich symbolism linking the dog with death, archaeology, mythology, and folklore have left us abundant testimony. With these we seek to provide the reader with a global and coherent view of seemingly distant concepts. And thus we see that, just as the dog is the universal companion of human beings in this world, so too it will be in the next. Wherever we look, dogs appear as guides on the soul’s journey after death to paradise, being the animal most frequently sacrificed in funerary rituals.

The Dog as Psychopomp in China

In China, the presence of dogs buried for ritual purposes as early as 9,000 years ago forms part of a continuous process of funerary symbolism—red pigment in some tombs, burial with wealth or everyday objects, preparation of the corpse for a long journey, and so on—which shows that from the remotest antiquity the inhabitants of China did not regard death as the end of existence, but as a change of dimension in which the person’s soul went to another world to rejoin the souls of the ancestors. That journey clearly implied a path, for which it became necessary to provide the deceased with a dog to guide them.

Burying someone with a dog became the standard ritual during the Early Bronze Age, and especially during the Shang dynasty, when it was one of the most common features of tombs. Nobles were buried with their pets, their wives, servants, ministers, and slaves, so as to continue enjoying their company in the new life. Dogs acted as guards or as hunting companions, for two types of dogs have been found in their tombs: young ones, about a year old, bred to be sacrificed, and older ones, sometimes even with bells on their collars, suggesting that they had accompanied their owners in life and were then to follow them in death. The bond must have been so close that sometimes they were placed on the coffin itself—in a clear reference to the household dog that sleeps at the foot of its master’s bed—beside the deceased, in a small waist-high pit situated beneath the dead person, or in the same pit, generally with the heads of both pointing in the same direction.

Opening of Chapter 5 of “The Magic of the Dog in China and the World.”

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China).

Last posts

Laozi’s Mother is the goddess who created the world

Laozi’s Mother is the goddess who created the world In Taoist thought, great mysteries are not explained with definitive statements, but with paradoxical images, fragmentary myths, and bodily metaphors. One such mystery is the origin of the world—and for Taoism, that...

Does the Daodejing Contain the Oldest Creation Myth of China?

Does the Daodejing Contain the Oldest Creation Myth of China? An introductory article on Chinese mythology asserts (twice) that the myth of the creation of Huangdi (the Yellow Emperor) should be considered one of China's creation myths, following the model of...

The Wenzi Begins: Echoes from a Forgotten Taoist Voice

The Wenzi Begins: Echoes from a Forgotten Taoist Voice The Wenzi (文子) is an ancient Daoist text attributed to a disciple of Laozi. Although its authenticity has been debated throughout history, its content clearly reflects the Daoist worldview and its influence on the...

A Humble Proposal for Rethinking Historical Periodization: To Go Beyond Dynasties in Chinese History

A Humble Proposal for Rethinking Historical Periodization: To Go Beyond Dynasties in Chinese History Historical narratives are never neutral. The way we divide time reflects not only the facts we choose to remember, but also the frameworks we use to interpret them. In...

The Primitivist: The Taoist Philosopher of Simplicity

The Primitivist: The Taoist Philosopher of Simplicity The Taoist classic Zhuangzi is not the work of a single philosopherAnyone who takes a closer look at the foundational works of Taoism will quickly discover that the book known as Zhuangzi was not entirely written...

Zhang Yongzheng, the master of deluding reality

Zhang Yongzheng, the master of deluding reality Reality is an illusion, say Buddhist texts. And each of Zhang Yonggzheng's (Gansu, 1978) works plays with this concept to remind us again and again that there is no immutable reality but a fluid universe of forms that...