The art of laying out gardens among the Chinese

In the 1740s, William Chambers travelled on three trading voyages to China with the Swedish East India Company. He was the first European to study Chinese architecture methodically. In a book published in 1757, Designs of Chinese buildings, furniture, dresses, machines, and utensils, he describes how the buildings and furniture were used, and explains the nature of Chinese taste, particularly with regard to the construction of gardens. Gardens was perhaps his favourite theme, as several years later, in 1772, he published Dissertation on Oriental Gardening.

Here we publish again his “Of the art of Laying out gardens among the Chinese”, part of the first book, as is a short essay very useful for the present students of Chinese art, gardens and architecture.

The gardens, which I saw in China, were very small ; nevertheless, from them, and what could be gathered from Lepqua, a celebrated Chinese painter, with whom I had several conversations on the subject of gardening, I think I have acquired sufficient knowledge of their notions on this head.

Nature is their pattern, and their aim is to imitate her in all her beautiful irregularities. Their first consideration is the form of the ground, whether it be flat, sloping, hilly, or mountainous, extensive, or of small compass, of a dry or marshy nature, abounding with rivers and springs, or liable to a scarcity of water; to all which circumstances they attend with great care, choosing such dispositions as humour the ground, can be executed with the least expense, hide its defects, and set its advantages, in the most conspicuous light.

As the Chinese are not fond of walking, we seldom meet with avenues or spacious walks, as in our European plantations. The whole ground is laid out in a variety of scenes, and you are led, by winding passages cut in the groves, to the different points of view, each of which is marked by a seat, a building, or some other object.

The perfection of their gardens consists in the number, beauty, and diversity of these scenes. The Chinese gardeners, like the European painters, collect from nature the most pleasing objects, which they endeavor to combine in such a manner, as not only to appear to the best advantage separately, but likewise to unite in forming an elegant and linking Whole.

Their artists distinguish three different species of scenes, to which they give the appellations of pleasing, horrid, and enchanted. Their enchanted scenes answer, in a great measure, to what we call romantic, and in these they make use of several artifices to excite surprize. Sometimes they make a rapid stream, or torrent, pass underground, the turbulent noise of which strikes the ear of the new comer, who is at a loss to know from whence it proceeds. At other times they dispose the rocks, buildings, and other objects that form the composition in such a manner, as that the wind passing through the different interstices and cavities, made in them for that porpose, causes strange and uncommon sounds. They introduce into these scenes all kinds of extraordinary trees, plants and flowers, form artificial and complicated echoes, and let loose different sorts of monstrous birds and animals.

In their scenes of horror, they introduce impending rocks, dark caverns, and impetuous cataracts running down the mountains from all sides, the trees are ill-formed, and seemingly torn to pieces by the violence of tempests; some are thrown down, and intercept the course of the torrents, appearing as if they had been brought down by the fury of the waters ; others look as if shattered and blasted by the force of lightening: the buildings are some in ruins, others half-consumed by fire, and some miserable huts dispersed in the mountains serve, at once, to indicate the existence and wretchedness of the inhabitants. These scenes are generally succeeded by pleasing ones. The Chinese artists, knowing how powerfully contrast operates on the mind, constantly practice sudden transitions, and a striking opposition of forms, colours, and shades. Thus they conduct you from limited prospects to extensive views; from objects of horror to scenes of delight ; from lakes and rivers, to plains, hills, and woods, to dark and gloomy colours they oppose such as are brilliant, and to complicated forms simple ones; distributing by a judicious arrangement the different masses of light and shade, in such a manner as to render the composition at once distinct in its parts, and linking in the whole.

Where the ground is extensive, and a multiplicity of scenes are to be introduced, they generally adapt each to one single point of view; but where it is limited, and affords no room for variety, they endeavor to remedy this defect, by disposing the objects so, that being viewed from different points, they produce different representations; and sometimes by an artful disposition, such as have no resemblance to each other.

In their large gardens they contrive different scenes for morning, noon and evening, erecting, at the proper points of view, buildings adapted to the recreations of each particular time of the day: and in their small ones (where, as has been observed, one arrangement produces many representations) they dispose in the same manner, at the several points of view, buildings, which, from their use point out the time of day for enjoying the scene in its perfection.

As the climate of China is exceeding hot, they employ a great deal of water in their gardens. In the small ones, if the situation admits, they frequently lay almost the whole ground under water; leaving only some islands and rocks: and in their large ones they introduce extensive lakes, rivers, and canals. The banks of their lakes and rivers are variegated in imitation of nature; being sometimes bare and gravelly, sometimes adorned with woods quite to the water’s edge. In some places flat, and covered with flowers and shrubs, in others steep, rocky, and forming caverns, into which part of the waters discharge themselves with noise and violence. Sometimes you see meadows covered with cattle, or rice-grounds that run out into the lakes, leaving between them passages for vessels; and sometimes groves, into which enter, in different parts, creeks, and rivulets, sufficiently deep to admit boats; their banks being planted with trees, whose spreading branches in some places form arbours, under which the boats pass. These generally conduct to some very interesting objects, such as a magnificent building; places on the top of a mountain cut into terraces; a casine situated in the midst of a lake; a cascade, a grotto cut into a variety of apartments, an artificial rock and many other such inventions.

Their rivers are seldom straight, but serpentine, and broken into many irregular points, sometimes they are narrow, noisy, and rapid, at other times, deep, broad, and flow. Both in their rivers and lakes are seen reeds, with other aquatic plants and flowers; particularly the Lyen-boa, of which they are very fond. They frequently erect mills, and other hydraulic machines, the motions of which enliven the scene. They have also a great number of vessels of different forms and sizes. In their lakes they intersperse islands, some of them barren, and surrounded with rocks and shoals, others enriched with everything that art and nature can furnish most perfect. They likewise form artificial rocks; and in competitions of this kind the Chinese surpass all other nations. The making them is a distinct profession: and there are at Canton and probably in most other cities of China, numbers of artificers constantly employed in this business. The stone they are made of comes from the southern coasts of China. : it is of a bluish cast, and worn into irregular forms by the action of the waves. The Chinese are exceeding nice in the choice of this stone, insomuch that I have seen several tael given for a bit no bigger than a man’s fist, when it happened to be of a beautiful form and lively colour. But these select pieces they use in landscapes for their apartments, in gardens they employ a coarser sort, which they join with a bluish cement, and form rocks of a considerable size. I have seen some of these exquisitely fine, and such as discovered an uncommon elegance of taste in the contriver. When they are large they make in them caves and grottos, with openings, through which you discover distant prospects. They cover them in different places with trees, shrubs, briars, and moss, placing on their tops little temples, or other buildings, to which you ascend by rugged and irregular steps cut in the rock.

When there is a sufficient supply of water, and proper ground, the Chinese never fail to form cascades in their gardens. They avoid all regularity in these works, observing nature according to her operations in that mountainous country. The waters burst out from among the caverns and windings of the rocks. In some places a large and impetuous cataract appears, in others are seen many lesser falls. Sometimes the view of the cascade is intercepted by trees, whose leaves and branches only leave room to discover the waters, in some places, as they fall down the side of the mountain. They frequently throw rough wooden bridges from one rock to another, over the deepest part of the cataract and often intercept its passage by trees and heaps of stones, that seem to have been brought down by the violence of the torrent.

In their plantations they vary the forms and colours of their trees; mixing such as have large and spreading branches with those of pyramidal figures, and dark greens with brighter, interspersing among them such as produce flowers, of which they have some that flourish a great part of the year. The weeping willow is one of their favourite trees, and always among those that border their lakes and rivers, being so planted as to have its branches hanging over the water. They likewise introduce trunks of decayed trees, sometimes erect, and at other times lying on the ground, being very nice about their forms, and the colour of the bark and moss on them.

Various are the artifices they employ to surprise. Sometimes they lead you through caverns and gloomy passages, at the issue of which you are, on a sudden, struck with the view of a delicious landscape, enriched with everything that luxuriant nature affords most beautiful. At other times you are conducted through avenues and walks, that gradually diminish and grow rugged, till the passage is at length entirely intercepted, and rendered impracticable, by bushes, briars, and stones; when unexpectedly a rich and extensive prospect opens to view, so much the more pleasing, as it was less looked for.

Another of their artifices is to hide some part of a composition by trees, or other intermediate objects. This naturally excites the curiosity of the spectator to take a nearer view; when he is surprized by some unexpected scene, or some representation totally opposite to the thing he looked for. The termination of their lakes they always hide, leaving room for the imagination to work and the same rule they observe in other compositions, wherever it can be put in practice.

Though the Chinese are not well versed in optics, yet experience has taught them that objects appear less in size, and grow dim in colour, in proportion as they are more removed from the eye of the spectator. These discoveries have given rise to an artifice, which they sometimes put in practice. It is the forming prospects in perspective, by introducing buildings, vessels, and other objects, lessened according as they are more distant from the point of view, and that the deception may be still more striking, they give a grayish tinge to the distant parts of the composition, and plant in the remoter parts of these scenes trees of a fainter colour, and smaller growth, than those that appear in the front, or fore-ground; by these means rendering what in reality is trifling and limited great and considerable in appearance.

The Chinese generally avoid straight lines, yet they do not absolutely reject them. They sometimes make avenues, when they have any interesting object to expose to view. Roads they always make straight, unless the unevenness of the ground, or other impediments, afford at least a pretext for doing otherwise. Where the ground is entirely level, they look upon it as an absurdity to make a serpentine road; for they say that it must either be made by art, or worn by the constant passage of travellers: in either of which cases it is not natural to suppose men would choose a crooked line when they might go by a straight one.

What we call clumps, the Chinese gardeners are not unacquainted with, but they use them somewhat more sparingly we do. They never fill a whole piece of ground with clumps; they consider a plantation as painters do a picture, and group their trees in the same manner as these do their figures, having their principal and subservient masses.

This is the substance of what I learnt during my stay in China, partly from my own observation, but chiefly from the lessons of Lepqua. And from what has been said it may be inferred, that the art of laying out grounds after the Chinese manner is exceedingly difficult, and not to be attained by persons of narrow intellects: for though the precepts are simple and obvious, yet the putting them in execution requires genius, judgment, and experience, a strong imagination, and a thorough knowledge of the human mind: this method being fixed to no certain rule, but liable to as many variations as there are different arrangements in the works of the creation.

Last posts

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art In fact, only a few moments are repeated very frequently in Tibetan paintings. In some versions there are eight—an auspicious number for Tibetans, corresponding to the Noble Eightfold Path and the eight...

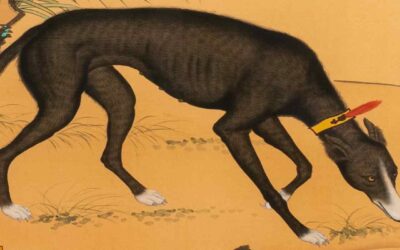

The Dog as Psychopomp in China

The Dog as Psychopomp in China One of the oldest human beliefs was that after death there existed an immaterial part of the person—later called the soul or spirit—that did not disappear with the body. Its origin may lie in the “presence” of the dead in dreams,...

An ambitious project to rewrite history

An ambitious project to rewrite history. It is what we see in Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene, The Nomadic Leviathan. A Critique of the Sinocentric Paradigm. Brill. Leiden. 2023. Now free to download in the publisher’s webpage. This book is a critique of a theoretical paradigm...