Spirits possession in ancient China.

I have just finished reading The Ancestors Are Drunk, a book by Jordan Paper. Perhaps one of the best books on the religion of China that can be found, because with every chapter, almost with every page, he opens new windows, providing new perspectives on this very interesting subject.

In China, the feeding of the dead served not only as one of the major lifecycle rituals but was also one of the most important rituals of the year-cycle as well. In this ceremony, a person chosen to incorporate the ancestor first drank and ate from the many prepared dishes until satiated and then announced the satisfaction of the spirits who subsequently departed. Then, the members of the clan ate the sacrificial food in an atmosphere of merriment.

All scholars of Chinese culture know that the character shi 尸, now used for «corpse» was originally a pictogram representing the impersonator of the dead, that is, the person representing the ancestor to whom meat and wine were offered, but in Jordan Paper’s book, this is the first time I see this process clearly described.

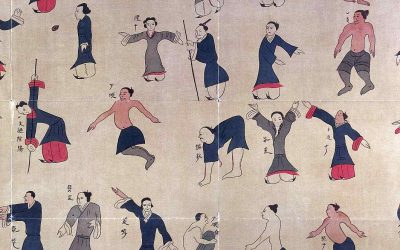

Spirit possession was part of elite sacrificial rituals. The ritual texts provide sufficient information that in the late Zhou period, the Personator of the Dead was possessed by the ancestral spirits to whom the sacrifice was being offered. The sequence of preparatory steps carried out by the impersonator prior to the sacrificial ritual, as well as the rites themselves, ensured that he reached an ecstatic state; that this state was mediumistic is definitely indicated by the context.

After chose by divination an appropriate day for offering sacrifice, the primary sacrificer, the Descendant, the son or daughter-in-law of the deceased, depending on the appropriate gender, and the other participants fasted for seven days to «bring the mind to a state of fixed determination» in the ceremony. On the fourth day of the fast, the impersonator was chosen from among the participants (grandson or granddaughter-in-law of the deceased) by divination, «inviting the spirit in his person to take some refreshment».

The impersonator, once selected, underwent an immediate increase of status and was treated as if he or she were already the ghost of the ancestor, «in passing whom it was required to adopt a hurried pace». According to their regulations, When an officer encountered one who was ready to personate the dead he should dismount from his carriage, and the ruler himself should do the same».

From that moment on, the impersonator dedicated his time to intense meditation sessions, during which he was instructed to remember and visualize all aspects of the deceased: «How and where he sat, how he smiled and spoke, what were their aims and views, what he delighted in, and what things he desired and enjoyed».

Given that the impersonator was already into the fourth day of a fast, albeit probably only partial, one can assume that alternate states of consciousness similar to those produced by hallucinogenic substances were engendered.

On the day of sacrifice, the impersonator was driven to the clan temple in a chariot and deferred to as if he or she were the deceased, although the text still refers to him or her as «one who is to incorporate the dead.» During the sacrifice, the impersonator several times ceremonially offered food and wine to the dead, which he ate and drank. Only after drinking nine cups of alcoholic beverage, did the impersonator communicate blessings to the Liturgist (master of ceremonies), who in turn announced these blessings to the other participants.

It is the inebriation of the shi that leads to the descent of the spirits into her or his body, as the alcoholic beverage made from millet had an alcoholic content of about 7 or 8 percent. Volumes of early Zhou bronze sacrificial cups nearly full, give an average of 5.5 to 5,25 ounces. Hence, a conservative estimate is that the shi consumed between 2.4 and 3.9 ounces of pure alcohol (equivalent to between 5 and 8 bar shots of eighty-proof liquor). When consumed over a ninety-minute period, six standard drinks or 75 grams of ethanol will generally cause slightly blurred vision and other signs of intoxication. Given that the alcohol consumption, although ingested with rich food, took place after a seven-day fast, the inebriation of the shi was ensured.

Alcohol, along with other drugs, is a common inducer of trance in a religious context. William James noted, «The sway of alcohol over mankind is unquestionably due to its power to stimulate the mystical faculties of human nature.»

The alcohol, the seven-day fast, the continuous meditation, including three days of visualization, the treatment of the impersonator by others as the deceased spirit, the sacrificial ritual, usually accompanied by the beating of drums and bells, and the cultural expectations, all combined to lead undoubtedly to the possession of the impersonator by the recipient of the sacrifice.

In this way, the grandson or granddaughter-in-law of the deceased became the means for the spirit of the deceased to descend to the sacrifice, to eat and drink the offerings, thereby becoming inebriated and extending blessings to the clan. Since these sacrifices were the most common elite religious ritual and given the frequency of ancestral sacrifices, virtually all of the elite in their youth, both male and female, would have been bonded to the clan by becoming the medium for the descent of the clan’s deceased members, most commonly in late adolescence. This experience undoubtedly enhanced the identification of elite individuals with the clan.

Therefore, trance experience was at least as important as normal consciousness in informing their world view of the members of the noble families. This explain why in Chinese popular religion, faith is unnecessary, for the people experience the immediate presence of the deities as they are embodied in possessed mediums.

Based on Jordan Paper, The Ancestors are drunk. Comparative approaches to Chinese religion. SUNY Press. 1995

Last posts

Laozi’s Mother is the goddess who created the world

Laozi’s Mother is the goddess who created the world In Taoist thought, great mysteries are not explained with definitive statements, but with paradoxical images, fragmentary myths, and bodily metaphors. One such mystery is the origin of the world—and for Taoism, that...

Does the Daodejing Contain the Oldest Creation Myth of China?

Does the Daodejing Contain the Oldest Creation Myth of China? An introductory article on Chinese mythology asserts (twice) that the myth of the creation of Huangdi (the Yellow Emperor) should be considered one of China's creation myths, following the model of...

The Wenzi Begins: Echoes from a Forgotten Taoist Voice

The Wenzi Begins: Echoes from a Forgotten Taoist Voice The Wenzi (文子) is an ancient Daoist text attributed to a disciple of Laozi. Although its authenticity has been debated throughout history, its content clearly reflects the Daoist worldview and its influence on the...

A Humble Proposal for Rethinking Historical Periodization: To Go Beyond Dynasties in Chinese History

A Humble Proposal for Rethinking Historical Periodization: To Go Beyond Dynasties in Chinese History Historical narratives are never neutral. The way we divide time reflects not only the facts we choose to remember, but also the frameworks we use to interpret them. In...

The Primitivist: The Taoist Philosopher of Simplicity

The Primitivist: The Taoist Philosopher of Simplicity The Taoist classic Zhuangzi is not the work of a single philosopherAnyone who takes a closer look at the foundational works of Taoism will quickly discover that the book known as Zhuangzi was not entirely written...

Zhang Yongzheng, the master of deluding reality

Zhang Yongzheng, the master of deluding reality Reality is an illusion, say Buddhist texts. And each of Zhang Yonggzheng's (Gansu, 1978) works plays with this concept to remind us again and again that there is no immutable reality but a fluid universe of forms that...