Linghu Zhuan’s Skepticism Leads Him to the Underworld

Linghu Zhuan was a man of great integrity who did not believe in gods or spirits. Whenever someone spoke of ghostly transformations or divine retribution in the afterlife, he refuted their words with compelling arguments. Near his residence lived an old man named Wu Lao, who had amassed great wealth through dishonest means. One night, Wu Lao fell gravely ill and died, but three days later, he came back to life. When asked about his experience, he claimed that because his family had performed Buddhist rituals and burned large amounts of spirit money, the officials of the underworld were pleased and allowed him to return to life.

Upon hearing this, Linghu Zhuan was outraged and exclaimed:

«So even the underworld is corrupt! I always thought greedy officials accepted bribes in the mortal world, but now it seems the same happens in the afterlife!»

A Poem as Criticism

Furious, Linghu composed a poem condemning the hypocrisy of divine justice:

A single string of paper money can bring back a soul;

Both public and private gates are open to corruption.

The gods may boast of virtue, but their light does not reach those below.

The poor receive no grace from Buddha, while the rich easily gain heavenly favor.

If good and evil bear no consequences, then let us gather gold and leave it to our heirs.

That night, as Linghu sat alone in his room, two ghostly messengers appeared before him and announced:

«The underworld summons you.»

Dragged to the Underworld

Despite his initial resistance, Linghu was dragged into the underworld. There, he found himself before a grand palace that resembled the imperial courts of the mortal world. The King of the Underworld, seated on a throne, condemned Linghu for his arrogance and ordered that he be thrown into the «Hell of Plowed Tongues» for defaming the divine court.

Realizing the gravity of his situation, Linghu pleaded for mercy. A minister dressed in green robes, known as the «Enlightened Judge,» interceded on his behalf:

«This man is stubborn and eloquent. If we punish him without justification, he will never submit. Allow him to present his case and acknowledge his mistakes.»

The Confession

Forced to write a confession, Linghu reflected deeply on his words and composed an extensive defense, explaining his skepticism and pointing out flaws in the system of divine justice. He argued:

«Since ancient times, humans have worshipped deities and built temples in their honor. However, if the heavens do not distinguish between good and evil, allowing the wicked to prosper while punishing the innocent, how can such a system inspire trust? My criticisms were not made out of malice but out of concern for fairness.»

Impressed by Linghu’s eloquence and sincerity, the King of the Underworld decided to release him, saying:

«Linghu Zhuan speaks with reason and should not be blamed. His resolve is unshakable, and his reasoning is sound. We shall pardon him and allow him to return to the mortal world.»

The Torments of Hell

Before departing, Linghu requested to tour the various hells. What he witnessed horrified him—sinners being skinned alive, disemboweled, boiled in oil, or subjected to endless torment. In one chamber, he saw adulterers tied to burning pillars, their flesh melting away. In another, monks and nuns who had broken their vows were transformed into animals. Finally, he came across treacherous ministers like Qin Hui of the Song Dynasty, eternally punished for betraying their rulers.

When Linghu awoke, he realized it had all been a dream. But upon visiting Wu Lao’s house, he learned that the old man had died during the night.

From «New Tales Under the Lamplight,» (剪燈新話) a collection of stories from the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). It was compiled by Qu You

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China). In my travels, I have specialized in Yunnan, Tibet, the Silk Road, and other lesser-known places. Feel free to write to me if you’re planning a trip to China. The agency I collaborate with offers excellent service at an unbeatable price. You’ll find my email below.

Last posts

Suicide Caused by the Sale of Wives in Late Imperial China

Suicide Caused by the Sale of Wives in Late Imperial China During the Qing dynasty, family relations were a constant cause of suicide, especially for women. Many of the distinctive features of Chinese marriage pushed women toward suicide, one of the most lethal being...

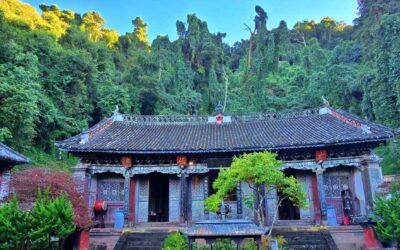

Discover the Treasure of Weibaoshan Mountain in Yunnan

Discover the Treasure of Weibaoshan Mountain in Yunnan Weibao Mountain (巍宝山) is one of the sacred mountains of Yunnan. Within its relatively small area it brings together a historical, artistic, natural, and monumental ensemble that makes it a unique place in China...

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven Those who know China—even if only through a brief trip—and who have visited the Temple of Heaven in Beijing will surely have been fascinated by the sober beauty of its buildings. Yet, whether on a crowded day or during a...

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art In fact, only a few moments are repeated very frequently in Tibetan paintings. In some versions there are eight—an auspicious number for Tibetans, corresponding to the Noble Eightfold Path and the eight...

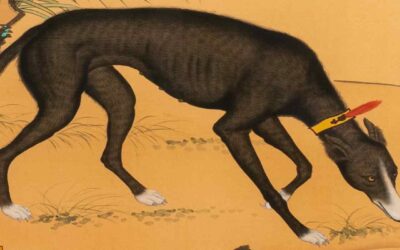

The Dog as Psychopomp in China

The Dog as Psychopomp in China One of the oldest human beliefs was that after death there existed an immaterial part of the person—later called the soul or spirit—that did not disappear with the body. Its origin may lie in the “presence” of the dead in dreams,...

An ambitious project to rewrite history

An ambitious project to rewrite history. It is what we see in Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene, The Nomadic Leviathan. A Critique of the Sinocentric Paradigm. Brill. Leiden. 2023. Now free to download in the publisher’s webpage. This book is a critique of a theoretical paradigm...