oyaaDuring a break in my studies, the afternoon of Christmas Eve I was looking through a cabinet in which I have some somewhat old books bought on various occasions at flea markets in Beijing and Shanghai. After running into Lewis Morgan’s «Ancient Society» and taking my destiny to his description of the democratic rules of the Iroquois Confederation, from which we still have much to learn, a little book of a little over a hundred pages called «Les Beaux Voyages – En Chine» caught my attention.

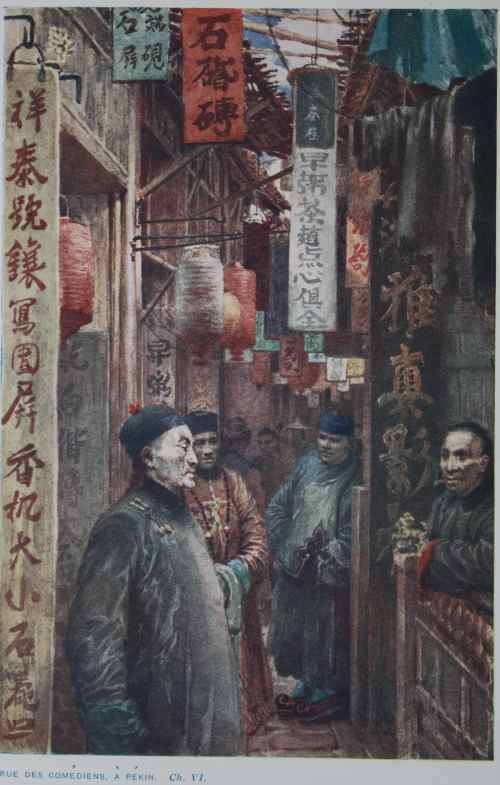

It contained beautiful illustrations that took me to that China anchored in the collective imagination of the West (and in mine before arriving in this country). The author Judith Gautier, daughter of the famous novelist Theophile Gautier, traveled through China and Japan, writing and translating works from these countries. The texts of this work are short, simple and direct.

I chose to translate and share one about dramatic art, among other things because I found the accompanying illustration fascinating. I’m sure some of you will share my enthusiasm.

History

It was in the 13th century, under the Tartar dynasty of the Yuan, that an emperor ordered to research all the plays written in the previous centuries, to choose the best ones, and to bring them together. It is then that the famous collection entitled «One hundred plays published under the Yuan» was formed. This is the most beautiful monument of the dramatic literature of the Chinese, and it still feeds the modern repertoire today.

All genres are represented in this collection: historical tragedy, domestic drama, mythological and fairy tales, comedy of character or morals, judicial dramas, religious dramas.

These plays are generally divided into four parts or acts, often preceded by a short prologue. The text is not divided into scenes, but the entrances and exits of the characters are indicated by these words–it goes up–it goes down; the asides are marked by this phrase: Speak with your back turned– the sung parts are engraved in characters larger than those of the spoken dialogue. In the writing of these pieces, all styles, all languages are used according to the subject. There is historical language, poetic or lyrical language, pompous, grave or familiar style.

Most of these dramas and comedies contain beauty of the first order, but almost all of them have, in our opinion, a compositional defect, which could well be a rule, as it is frequently found in Chinese plays: it is to be divided in two. In the first act, intrigue and crime triumph, in the last act revenge and punishment are carried out. The heroes of the beginning have become old, their sons, sometimes their grandsons, who were seen as children in the first acts, or who were not yet born, are men and take in hand the threads of the plot that they unravel, to put things back more or less as they were at the beginning of the play. This system has the disadvantage of sharing interest; the young man, who is introduced to the audience late in the evening, does not always have time to attract sympathy.

The actors

The profession of the actors is very hard in China; they are the true slaves of the director of the troupe, who leads them hard and leaves them with little leisure time. They each have their own job; there are: the Tchin-Mo, leading role; the Siao-Mo, young man; the Ouai, dignitary; the Pai-lo, old father; the Tchen, comic character. But when the troupe is small, they are required to play two and three roles in the same play.

The women do not appear on the stage; the cross-dressing of the boys from 16 to 19 years old into girls or women, manages to produce a complete illusion. The young men chosen for these roles are handsome, graceful, small and thin, they let their hair grow, skillfully make up their hair, and push the coquetry to the point of putting on fake feet. This is how they proceed: the heel rests on a piece of wood that holds the foot, the toe down in an almost vertical position, the toe alone is wearing a small silk shoe embroidered with gold.

Rolled up strips, the puffy pants, tied in the middle of the instep, conceal a little the fraud and the embarrassed gait, which results from these arrangements, helps the illusion. How many Chinese ladies, how many wealthy women and merchants have resorted to this artifice! like the young actors.

In large cities–in Beijing, in Shanghai–there are fixed theaters, and they are the best equipped in the world for the pleasure and well-being of the spectators. In Beijing, they are grouped in the same district, and the actors almost all live in the street of the theaters.

When you pass by in the morning, you can hear them declaim their roles, or imitate the rooster crowing over and over again. It seems that there is nothing like it to strengthen the voice. The theaters, in general, do not have a special troupe, itinerant troupes play in one or the other; more often than not, they run around the province and are hired by the prefects or by the monks, on the occasion of a popular festival, or in the homes of rich individuals who want to follow the pleasure of a feast with the nobler pleasure of a performance. In this case, at the moment of sitting at the table, we see five actors, richly dressed, prostrate themselves. Then one of them presents the master of the house with a book containing in gold letters the titles of about sixty plays that the troupe is able to perform on the spot: this list is circulated and the most qualified guest designates the play he likes best.

Plays with a moral teaching

All dramatic works, the masters say, must have a serious meaning and a moral purpose. A play without morality is ridiculous… They must present the noblest teachings of history, to those who cannot read, show paintings, real or supposed of life, capable of inspiring the practice of virtue. An immoral play is a crime. Its author is punished, in the other world, and his atonement lasts as long as his play is performed on earth.

Already in the eighth century, in the palace of Chang’an, the emperor Ming Yuan had a superb theater built, in which he performed in person.

He himself took care of his troupe of actors, directing the studies and rehearsals. They took place most often in a part of the parks that was called «the Pear Tree Enclosure». That’s why actors are still sometimes called «The students of the pear tree enclosure.»

Passion for the stage in the Tang Dynasty

The court’s infatuation with the theatrical art quickly won over high-ranking officials and private individuals. Everyone wanted to have his own private theater, his actors and his troupe of dancers. This soon became a madness that had to be suppressed; among other things, the number of dancers that each one, according to his rank, was allowed to maintain was limited: 64 were granted to the emperor, 36 to princes of the blood, 16 to ministers, 8 to members of the nobility, and only 2 to scholars and private individuals.

The ballets, at that time, were extremely magnificent and bore pompous titles. They were entitled: The Portico of the Clouds; The Great Whirlwind; The Cadencious, apparently the most graceful dance of antiquity; The Great Dynastic, this one slow and engraved; The Beneficent; The Warrior; The Dance of the Feather, the Shield, and the Colored Banners. There was one, that of the Dragon, whose movements took place in the water, and another, where a bull was represented, with which the dancer struggled while holding his horns.

This emperor, Ming Yuan, who did not disdain to climb on the boards, is still considered today, as the patron of theater and actors. His statuette is always placed backstage on a small altar where incense is always burning. Each actor, before entering the stage, piously salutes the image of the one who, ten centuries ago, was benevolent to them, and protected the artists. And nothing is more touching than the expression of this recognition that never ends.

Last posts

Buddhist Immersion from Shanghai: No Need to Board a Plane—Paradise Is Right at Your Doorstep

Buddhist Immersion from Shanghai: No Need to Board a Plane—Paradise Is Right at Your Doorstep Residents of Shanghai eager to learn more about Buddhist art and history often think they must undertake long journeys to reach the sacred mountains of this religion. What...

The Lost Mythology of Ancient China

The Lost Mythology of Ancient China Reconstructing the mythology of ancient China is a painstaking task that tries to characterize some legendary figures and situations based only on the few sentences about them found in later works by philosophers and historians. The...

How a Eunuch Was Created in 19th-Century China

How a Eunuch Was Created in 19th-Century China A wealthy eunuch would purchase a boy from a poor family. This boy had to be between seven and ten years old. He would be kept confined for two weeks and subjected to a very strict diet; he ate little. Use of...