An ambitious project to rewrite history.

It is what we see in Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene, The Nomadic Leviathan. A Critique of the Sinocentric Paradigm. Brill. Leiden. 2023. Now free to download in the publisher’s webpage.

This book is a critique of a theoretical paradigm – the Sinocentric paradigm – that shapes scholarly understanding of the origin and nature of state, empire, and tribal organization. The Sinocentric paradigm represents a habit of thought, and a regime of truth, that have long been established in academia. Though it has increasingly been questioned, it remains the predominant academic vision, guiding, informing, structuring, and shaping scholarly understanding and inquiries. This critique debunks the paradigm, and argues for a rival perspective – that of conquest theory.

In particular, this critique exposes the Sinocentric paradigm as a myth that rationalizes the existing order as natural and inevitable. It also suggests that humanity is not on the path of inexorable progress inherent in notions of evolution. The evolutionary materialist scheme – which preaches the incessant betterment of the human condition and attributes it to the invisible hand of evolution powered by economic growth – is revealed as false. It was not the invention of agriculture, the growth of wealth and populations, or the rise of property and class differentiation that led to the state and determined the course of human history. Inequality and the state are not the creations of the economy, and social and political order is not a reflection and embodiment of economic order. Nor was it areas of circumscribed agricultural land and sedentism that gave birth to the state; we can reject both this theory and its corollary – that China or the likes (hence the Sinocentric paradigm) built the early states.

This book argues for the nomadic origin of the state – hence the title, The Nomadic Leviathan. The book contends that it was the invention of extrahuman transportation such as the domestication of pastoral livestock that led to inequality and the state. It was the rise of the warband that led by a charismatic warlord – the archetype for political power and authority – and the forceful subjugation and integration that created the state. The state is fundamentally a relation of political domination – domination by virtue of authority, that is, power to command and duty to obey – based ultimately upon a monopoly of violence over life and liberty. Not only does the political exists on its own terms but also political relationships are primary and fundamental, and it is the political constitution that determines and defines the social and economic. The existing order is neither natural nor inevitable; yet it is bound to last for as long as people believe it to be natural, normal, or inevitable. This book is not the first to argue for the nomadic origin of the state – the conquest theory of the state argued so – nor is this work another example of the “we got stuck” variety of argument (Graeber and Wengrow 2021: 514). Rather, the book offers a radically different understanding of the origin and nature of the state and political organization, and thus advances a fundamentally different vision of human history: one that sees the human journey as neither fated, nor as doomed and ‘stuck’.

The book analyzes two rival theories of the origin and nature of the state and tribalism – the conquest theory and the Sinocentric paradigm. The latter is scrutinized in the light of the former, also taking into account recent advances in scholarship including those in archaeology. It provides a detailed examination of how these theories define and conceptualize the state, empire, and tribal organization, and their origins; outlines the genesis and development of their theoretical ideas and schemes; and analyzes the ways in which these theories inform and shape historical inquiries relating to Inner Asia and China. This analysis identifies the Sinocentric scheme as the dominant paradigm, having displaced the conquest theory and established itself as the vision for the premodern political world. It reveals the fundamental anomalies that this paradigm has created, exposes major contradictions within it, and demonstrates its untenability. Since theories develop in dialogue with preexisting ideas and theories, the analysis here follows that development. The work also explores the agenda that lies behind the initial Sinocentric scheme, revealing a project that deliberately sought to interpret the past from a particular perspective, so to advance a specific political agenda.

In highlighting the key ideas of the main representatives of the conquest theory, and their critique of historical materialism, this book resurrects the conquest theory and, with it, the idealistic understanding of history. By advancing the idea of extrahuman transportation as crucial – well supported by recent advances in archaeology – it reinforces conquest theory’s argument for the nomadic origin of the state. Both the origin of the state, located in a chronic state of war and military differentiation, and the archetypes of the state, found in the military constitution of the warband led by a warlord and in the political authority of imperium, clearly argue for the conquest theory. Not only do the categorical separation of the political and the economic, and the diametric contrast between political and economic forms of domination speak against the materialistic conception of history, but so too does the primacy of the political over the economic. The argument of ‘belief’ as the source of not only the distinction between the political and the economic, but also of legitimate authority, is a definite argument for the idealistic conception of history. Charisma, and charismatic revelation and revolution, stand at the beginning of all of them and indeed of history itself. Weber’s scheme argues thus, and this book argues that his scheme is not only the most elaborate of the conquest theories, but also the idealistic conception of history that aims to replace the evolutionary materialistic conception of history. This book liberates Weber’s scheme from the evolutionary materialist appropriation that rendered it unrecognizable and the treatment that reduced it to serving to what it aimed to replace and relegated its main agent (charisma), and the author of history, to a feature of prehistoric primitivity.

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China).

Last posts

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven Those who know China—even if only through a brief trip—and who have visited the Temple of Heaven in Beijing will surely have been fascinated by the sober beauty of its buildings. Yet, whether on a crowded day or during a...

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art In fact, only a few moments are repeated very frequently in Tibetan paintings. In some versions there are eight—an auspicious number for Tibetans, corresponding to the Noble Eightfold Path and the eight...

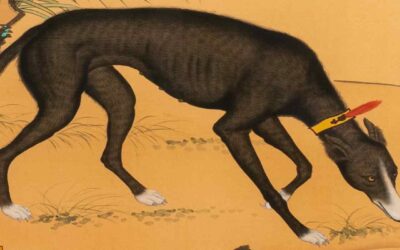

The Dog as Psychopomp in China

The Dog as Psychopomp in China One of the oldest human beliefs was that after death there existed an immaterial part of the person—later called the soul or spirit—that did not disappear with the body. Its origin may lie in the “presence” of the dead in dreams,...

Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture

Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture In early November 2022 my friend, the psychiatrist Luz González Sánchez, told me that she was preparing a lecture on suicide. On the 8th of that same month, during a quiet moment, I made a brief...

The Tibetan Deity with a Horse Face

The Tibetan Deity with a Horse Face During my most recent journey to Tibet, someone pointed out to me in a temple a deity who bore a small horse upon his head. I knew that this protector is called Hayagriva, and that he is sometimes referred to as “Horse-Headed” or...

The Horse God as One of the Most Popular Deities in China

The Horse God as One of the Most Popular Deities in China If a visitor goes to the Great Wall at Juyongguan, the section closest to Beijing and one of the most historically significant, and takes the time to explore the complex of structures carefully—a...