A Humble Proposal for Rethinking Historical Periodization: To Go Beyond Dynasties in Chinese History

Historical narratives are never neutral. The way we divide time reflects not only the facts we choose to remember, but also the frameworks we use to interpret them. In Chinese history, the convention of organizing events and developments by dynasties has long been accepted as standard practice. Yet this approach—while convenient—carries with it significant limitations. This modest proposal invites readers to consider a shift away from dynastic labels toward a more precise, thoughtful periodization grounded in centuries and specific years. It is not a rejection of tradition for its own sake, but a call to update our analytical tools in step with modern historiographical standards.

It is time we critically reassess the persistent habit of organizing Chinese history through the lens of dynastic chronology. While this method has dominated historical writing for centuries, it has become increasingly clear that dividing history by dynasties is not only imprecise but intellectually outdated.

- Dynasties Span Centuries—But Time Is Not Uniform

To speak of «the Tang Dynasty» or «the Qing Dynasty» as monolithic entities flattens the complex social, political, and cultural transformations that occurred within them. Some dynasties lasted for centuries—the Zhou for nearly 800 years, the Qing for nearly 300. To discuss the early Tang with the same conceptual toolkit as the late Tang is akin to treating early medieval Europe and the Enlightenment as one and the same. Conditions at the beginning and end of a dynasty can be radically different, yet this nuance is lost in the dynastic shorthand.

- A Method Out of Step with Modern Historiography

This dynastic framing belongs to a pre-modern mode of thinking, one closely tied to imperial legitimacy and Confucian political theory. Modern historiography has, in other regions and disciplines, moved away from periodizations tied to ruling houses or religious dispensations. In physical anthropology, for example, outdated racial typologies like “Caucasoid” or “Mongoloid” have been discarded in favor of more precise, scientifically grounded classifications. Yet in Chinese historical studies, the dynasty-as-historical-unit continues to dominate, despite its conceptual fragility.

- Dynastic Shifts Are Sometimes Cosmetic

Ironically, the transitions between dynasties—so often emphasized in surveys and textbooks—can sometimes represent less real change than internal transformations within a single dynasty. The fall of the Northern Song and rise of the Southern Song, for example, involved substantial continuity in administrative structures and elite culture. On the other hand, the mid-Ming period may show more structural change than the Qing transition. Treating dynasties as hard boundaries ignores the porousness and contingency of historical processes.

- A Thousand-Year Leap, No Questions Asked

Perhaps the most egregious consequence of dynastic periodization is how it enables sloppy narrative jumps. It is not uncommon to see generalist writers or non-China specialists leap from the Han to the Tang, or from the Tang to the Qing—skipping entire centuries without reflection, simply because a dynasty ended and another began. This is historical writing by placeholders, not by inquiry.

- A Shortcut for the Unfamiliar

Writers unfamiliar with Chinese history often rely on dynasties as narrative crutches, not because they are meaningful, but because they offer a prepackaged frame. But this leads to absurd constructions—jumping a thousand years between the Han and the Song with no justification other than the dynastic timeline. We would never write the history of Europe as “from the Merovingians to the Habsburgs” without context. Why accept such crude leaps when writing about China?

- Time Is Not Measured by Thrones Alone

History must be a study of societies and their rhythms—not merely the succession of rulers. Other disciplines long ago abandoned ruler-centric or lineage-centric timeframes. Even China itself took this step with the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, abandoning the imperial calendar and adopting the international Gregorian system. This was not just administrative pragmatism—it was a declaration of historical modernity, of entering global time rather than remaining confined within the temporal structures of imperial legitimacy.

7. Dynastic periodization makes Chinese history harder to understand for the general public

Just like what happens with Egyptian history, dynastic names can alienate general readers. When someone sees «during the Song dynasty,» they often have no idea whether that refers to the 2nd or the 12th century. That confusion is why many authors feel the need to include the dates of each dynasty the first time they mention them—or even add a table at the end of the book. This reliance on clarification highlights how unintuitive the dynastic system is, turning the reading of Chinese history into an elitist matter reserved for a small group of specialists, instead of an accessible cultural experience for all.

8. Dynastic periodization also creates confusion among specialists, blurring the internal chronology of long-lasting dynasties

Dynasties can last for centuries, and yet they are often treated as unified blocks. This habit can lead even expert historians to lose sight of when things actually happened within them. Was a given economic reform introduced early or late in the dynasty? Did a major religious movement arise under a strong central government or amid decline? These distinctions are crucial—but when events are labeled simply as “Tang” or “Ming,” the temporal nuances are often lost. In this way, dynastic labels not only obscure ruptures between dynasties, but also flatten the rich and evolving histories that unfold within them.

A Modest Proposal: Count in Years and Centuries

Let us begin speaking of Chinese history in centuries, decades, and years—units used globally and in all other domains of historical writing. Instead of “during the Ming,” say “in the early 17th century.” Instead of “under the Tang,” say “in the late 700s.” Such language encourages clarity, continuity, and cross-cultural comparison. It also restores agency to events, people, and movements, rather than binding them to the aura of an emperor’s court.

This is not a call to erase dynasties from our vocabulary altogether—of course, they remain important. But we must decenter them from the architecture of our historical thinking. It’s time for a shift. Chronological clarity, not imperial shorthand, should guide our narratives

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China). Yo can see my mis videos in Youtube, and more pictures about China in Instagram (pedroyunnan).

In travel, I have specialized in Yunnan, Tibet, the Silk Road, and other lesser-known places. Feel free to write to me if you’re planning a trip to China. The agency I collaborate with offers excellent service at an unbeatable price. You’ll find my email below.

Last posts

A Giant Mandala in the Heart of Tibet

A Giant Mandala in the Heart of Tibet The Palkor of Gyantze is one of Tibet’s great marvels and a unique jewel of universal architecture and art. Its shape, scale, and iconography defy comparison with any other construction. Amidst some of the highest mountains of...

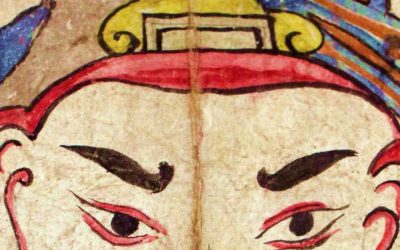

The Largest Collection of Paintings from ancient China

The Largest Collection of Paintings from ancient China No one doubts that pictorial art has existed in China since time immemorial. In fact, some painted pottery vessels, several thousand years old, continue to intrigue archaeologists who try to unravel their ultimate...

The Real Situation of Women in the Qing Dynasty

The Real Situation of Women in the Qing Dynasty Guo Songyi[1] has raised several important points about the situation of Chinese women during the Qing dynasty—points that could fundamentally reshape how both the public and academic researchers view this period. What...

Laozi’s Mother is the goddess who created the world

Laozi’s Mother is the goddess who created the world In Taoist thought, great mysteries are not explained with definitive statements, but with paradoxical images, fragmentary myths, and bodily metaphors. One such mystery is the origin of the world—and for Taoism, that...

A detective story among the Dai nationality

A detective story among the Dai nationality Among the rich folk literature of the Dai nationality, living in the south and western borders of Yunnan province, mainly in the Xishuangbanna and Dehong Autonomous Prefectures the tales of the tricksters[1] Aisu and Aixi...

Does the Daodejing Contain the Oldest Creation Myth of China?

Does the Daodejing Contain the Oldest Creation Myth of China? An introductory article on Chinese mythology asserts (twice) that the myth of the creation of Huangdi (the Yellow Emperor) should be considered one of China's creation myths, following the model of...