A Giant Mandala in the Heart of Tibet

The Palkor of Gyantze is one of Tibet’s great marvels and a unique jewel of universal architecture and art. Its shape, scale, and iconography defy comparison with any other construction.

Amidst some of the highest mountains of central Tibet, on the ancient trade route linking Lhasa with India, lies the small town of Gyantze. There stands one of the most singular and dazzling monuments of the Buddhist world: the Palkor Chöde. With a silhouette that astonishes from the very first glance, the Palkor is neither palace nor fortress, neither monastery nor temple, but rather a kind of three-dimensional architectural mandala: a kumbum.

- An Architectural Form Without Parallel

While most Tibetan temples follow horizontal layouts inspired by Indian or Chinese models, the Palkor rises like a stepped pyramid of multiple levels, each containing rows of chapels. This structure follows a symbolic design, representing a universe through which the pilgrim ascends toward enlightenment. The term kumbum literally means “one hundred thousand images,” and in the case of the Palkor, the name is no exaggeration.

- An Artistic Treasure Without Equal

The interior of the kumbum contains 108 chapels distributed across six concentric levels. Each one is adorned with frescoes, statues, and mandalas that, on their own, could justify the existence of an entire religious center. In fact, anywhere else in the world, a single one of these chapels would be enough to attract pilgrims, scholars, and art lovers alike. The mural paintings that cover its walls—rendered in the Nepali-Tibetan style of the 15th century—still preserve a vividness of color and detail that has withstood centuries of weather, war, and neglect. Many of these images offer a compendium of cosmology, medicine, tantric ritual, and visions of the afterlife.

- History of Its Construction

The Palkor was built between the late 14th and mid-15th centuries under the patronage of the prince of Gyantze, Rabten Kunzang Phak, during a period of relative political stability and cultural openness in Tibet. It was a time when multiple Buddhist schools coexisted, and the monastery annexed to the kumbum was home to at least three traditions: Gelug, Sakya, and Kagyu. This coexistence explains the rich iconographic and doctrinal diversity found within, making the Palkor a living testament to a plural and dynamic Tibet.

- Symbolism in the Tibetan World

The Palkor is not merely a temple: it is an architectural mandala to be walked through, a physical visualization of the path to enlightenment. Ascending its levels is like progressing through the stages of tantra—from the outer circles of protection to the central deities who embody emptiness and compassion. Each chapel serves as a gateway to a specific teaching, and the whole structure forms a miniature cosmos. Its design, layout, and ritual function make it a monument of profound symbolic depth.

Visiting the Palkor Today

Despite the ravages of time and the iconoclastic campaigns of the 20th century, the Palkor still stands—lofty and magnificent, a reliquary of wisdom and beauty. Climbing its levels, pausing in its chapels, and attempting to uncover its mandalic meaning is a transformative experience. For those who observe it with care, the Palkor is not merely a monument—it is a silent teaching, a vertical pilgrimage to the heart of Tibetan Buddhism.

The mandalic structure of the Palkor recalls, in both function and symbolism, the great monument of Borobudur in Indonesia. Both can be read as three-dimensional mandalas, designed for the pilgrim to physically experience the transformations that masters achieve on the psychological plane.

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China). In my travels, I have specialized in Yunnan, Tibet, the Silk Road, and other lesser-known places. Feel free to write to me if you’re planning a trip to China. The agency I collaborate with offers excellent service at an unbeatable price. You’ll find my email below.

Last posts

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven Those who know China—even if only through a brief trip—and who have visited the Temple of Heaven in Beijing will surely have been fascinated by the sober beauty of its buildings. Yet, whether on a crowded day or during a...

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art In fact, only a few moments are repeated very frequently in Tibetan paintings. In some versions there are eight—an auspicious number for Tibetans, corresponding to the Noble Eightfold Path and the eight...

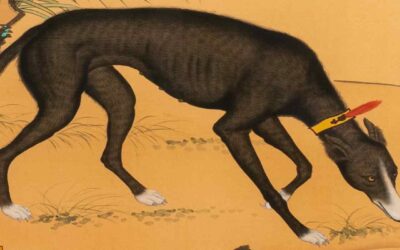

The Dog as Psychopomp in China

The Dog as Psychopomp in China One of the oldest human beliefs was that after death there existed an immaterial part of the person—later called the soul or spirit—that did not disappear with the body. Its origin may lie in the “presence” of the dead in dreams,...

An ambitious project to rewrite history

An ambitious project to rewrite history. It is what we see in Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene, The Nomadic Leviathan. A Critique of the Sinocentric Paradigm. Brill. Leiden. 2023. Now free to download in the publisher’s webpage. This book is a critique of a theoretical paradigm...

Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture

Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture In early November 2022 my friend, the psychiatrist Luz González Sánchez, told me that she was preparing a lecture on suicide. On the 8th of that same month, during a quiet moment, I made a brief...

The Tibetan Deity with a Horse Face

The Tibetan Deity with a Horse Face During my most recent journey to Tibet, someone pointed out to me in a temple a deity who bore a small horse upon his head. I knew that this protector is called Hayagriva, and that he is sometimes referred to as “Horse-Headed” or...