Suicide Caused by the Sale of Wives in Late Imperial China

During the Qing dynasty, family relations were a constant cause of suicide, especially for women. Many of the distinctive features of Chinese marriage pushed women toward suicide, one of the most lethal being the husband’s legal ability to sell his wife. In the Qing period, the sale of women and children was illegal, although it was permitted under certain circumstances.

Circumstances under which a wife could be sold

A husband could sell his wife if she had committed adultery, attempted to run away, agreed to be sold as a servant to another household, or if he himself was ill, disabled, or living in extreme poverty. We should remember that, having entered marriage without their feelings being taken into account, in some cases sale could offer women an opportunity to improve their situation, even allowing them to escape into a new life with a partner of their own choosing. In other cases, the fear of being sold kept them in a state of constant anxiety and extreme insecurity, and among the poor there was often no clear distinction between marriage and the trafficking of women (Sommer 2015: 2).

A last resort in times of family ruin

Sometimes destitution and extreme poverty were so widespread that wives became the family’s last economic resource. Drought, war, tax increases, or epidemics plunged thousands of households into absolute misery, forcing husbands to sell their wives or daughters in order to survive.

The tragedy of Nie Yide

Because wives could only be sold under certain circumstances, many conflicts arose—tragedies that have come down to us in compilations of judicial cases. In 1774, in Hengyang County, Hunan, the brothers of the peasant Nie Yide forced him to sell his wife, Chang Shi, to compensate them for an accidental fire she had caused. Nie did not want to do so, but had no choice. Chang Shi also refused to be sold and fled to her father’s house. Her husband went to retrieve her and explained the situation to his father-in-law. The latter, believing that his daughter was living a miserable life and might be better off with a new husband, did not object. When Chang Shi was persuaded that her husband would not sell her, she returned home. But on the way she learned the truth and threw herself into a lake in an attempt to commit suicide. Rescued by her companions, she insisted that she would rather die than remarry. On arriving home, her husband and his brothers watched her all night to prevent her from fleeing or killing herself. The next day Chang Shi refused to eat and tried to escape. Her distraught husband begged his brothers to cancel the deal, but they insisted it was too late, as the money had already been received. They then tied Chang Shi to the bed and gagged her so that they could sleep. The next morning she was dead, having suffocated on the gag (Bodde and Morris 1967: 231).

In a Hunan case from 1830, Huang Dexiu sold his wife Chen Shi in marriage, causing her to hang herself. In another case from Anhui in 1831, Cao Yushu sold his wife to Wang Chaofu, who “used force to take her home and consummate the marriage,” after which she committed suicide “out of shame and indignation.” Both husbands were sentenced to one hundred strokes of the heavy bamboo and three years of penal servitude (Bodde and Morris 1967: 315).

Threats of suicide to force a sale

Threats of suicide could also be used by women to bring about their own sale. In an 1810 case from Linyu County, the peasant Ma Siliang sold his wife after she jumped into a well and had to be pulled out by neighbors. She was not injured (and made sure to jump in front of witnesses who would rescue her), but her dramatic gesture convinced her husband. She resented their poverty and constantly caused trouble, saying she wanted to marry another man so as not to suffer anymore (Bodde and Morris 1967: 217).

Wives sold into prostitution

Even worse were cases in which wives were sold into prostitution (not always openly declared) to criminal groups that managed to circumvent the law to maintain their businesses. Despite being punishable by law, this became very common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It could also serve as a punishment for women who failed to meet the expectations of their husbands or their families.

From Chapter 9 of The Culture of Suicide in China and the Fall of the Imperial Regime (La cultura del suicidio en China y la caída del régimen imperial)

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China).

Last posts

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven Those who know China—even if only through a brief trip—and who have visited the Temple of Heaven in Beijing will surely have been fascinated by the sober beauty of its buildings. Yet, whether on a crowded day or during a...

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art In fact, only a few moments are repeated very frequently in Tibetan paintings. In some versions there are eight—an auspicious number for Tibetans, corresponding to the Noble Eightfold Path and the eight...

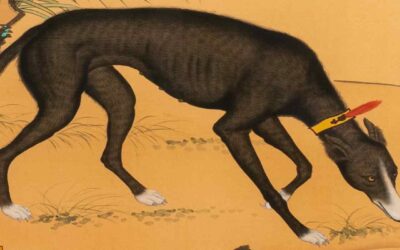

The Dog as Psychopomp in China

The Dog as Psychopomp in China One of the oldest human beliefs was that after death there existed an immaterial part of the person—later called the soul or spirit—that did not disappear with the body. Its origin may lie in the “presence” of the dead in dreams,...

An ambitious project to rewrite history

An ambitious project to rewrite history. It is what we see in Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene, The Nomadic Leviathan. A Critique of the Sinocentric Paradigm. Brill. Leiden. 2023. Now free to download in the publisher’s webpage. This book is a critique of a theoretical paradigm...

Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture

Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture In early November 2022 my friend, the psychiatrist Luz González Sánchez, told me that she was preparing a lecture on suicide. On the 8th of that same month, during a quiet moment, I made a brief...

The Tibetan Deity with a Horse Face

The Tibetan Deity with a Horse Face During my most recent journey to Tibet, someone pointed out to me in a temple a deity who bore a small horse upon his head. I knew that this protector is called Hayagriva, and that he is sometimes referred to as “Horse-Headed” or...