The truth about the Great Wall

What would later come to be known as the Great Wall formed as a response to increased Mongol raiding after Esen was killed in 1455. Having failed to capitalize on the capture of Zhengtong, Esen lost the political momentum that had held the disparate Mongol groups together. The ensuing civil war spread into Chinese territory as warring factions sought economic resources to support their military efforts. One faction moved into the Ordos region, now no longer supervised by a Ming garrison, placing the Mongols squarely against Ming territory. The Mongols still wanted to present tribute, and receive gifts in return, and to trade with the Ming; failing that, they raided. Meanwhile, the Ming court was Itself distracted by Zhengtong’s return to power in a coup d’état in 1457. Jingtai died of illness or was poisoned, and Zhengtong resumed as emperor with a new reign period: Tianshun.

It was difficult to establish a consistent policy toward the Mongols given their ongoing wars, a situation further exacerbated by Tianshun’s weak leadership. A proposal to launch a campaign to retake the Ordos and establish garrisons, fortified positions, and agriculture, and so maintain control of the area, was approved, but nothing came of it. Further proposals for offensive action were sanctioned and left unfulfilled. In the interim, some commanders suggested pulling back to more hilly areas to the south that were easier to defend. This too was rejected. In 1471, Yu Zijun submitted a plan to build wall between Yansui and Qingyang to aid in defense.

A wall-based defense was expensive to construct and of questionable effectiveness. Yet the court did not have the will to devote the economic and military resources necessary to launch its desired offensive. Wall building won out because it was cheaper than any offensive; the first two long walls were finished in 1474, one 129 miles long and the other 566 miles long. Over the next century more and more walls were built; in many places there were actually two lines, with forts and watchtowers, evolving into what we now know of as the Great Wall. Although the walls were useful, they were never intended as a complete solution to the Mongol problem. The difficulty was that the same economic, political and military problems continued to obtain, leading successive generations through the same debate that put additional resources into wall building. The short-term question was how to make the wall system more effective, since the long-term problem of the Mongols could not, apparently, be solved.

Peter Lorte. War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China 900-1795. Routledge. London and New York. 2005. P. 124

About me: I have spent 30 years in China, much of the time traveling and studying this country’s culture. My most popular research focuses on Chinese characters (Chinese Characters: An Easy Learning Method Based on Their Etymology and Evolution), Matriarchy in China (there is a book with this title), and minority cultures (The Naxi of Southwest China). In my travels, I have specialized in Yunnan, Tibet, the Silk Road, and other lesser-known places. Feel free to write to me if you’re planning a trip to China. The agency I collaborate with offers excellent service at an unbeatable price. You’ll find my email below.

Last posts

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven Those who know China—even if only through a brief trip—and who have visited the Temple of Heaven in Beijing will surely have been fascinated by the sober beauty of its buildings. Yet, whether on a crowded day or during a...

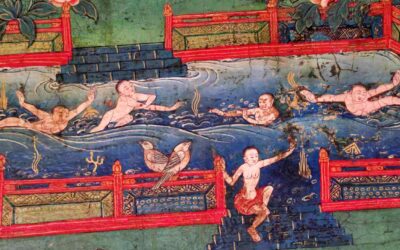

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art

Most Frequent Scenes from the Life of the Buddha in Tibetan Art In fact, only a few moments are repeated very frequently in Tibetan paintings. In some versions there are eight—an auspicious number for Tibetans, corresponding to the Noble Eightfold Path and the eight...

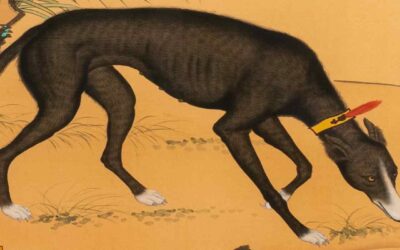

The Dog as Psychopomp in China

The Dog as Psychopomp in China One of the oldest human beliefs was that after death there existed an immaterial part of the person—later called the soul or spirit—that did not disappear with the body. Its origin may lie in the “presence” of the dead in dreams,...

An ambitious project to rewrite history

An ambitious project to rewrite history. It is what we see in Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene, The Nomadic Leviathan. A Critique of the Sinocentric Paradigm. Brill. Leiden. 2023. Now free to download in the publisher’s webpage. This book is a critique of a theoretical paradigm...

Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture

Why I devoted more than a year to researching suicide in Chinese culture In early November 2022 my friend, the psychiatrist Luz González Sánchez, told me that she was preparing a lecture on suicide. On the 8th of that same month, during a quiet moment, I made a brief...

The Tibetan Deity with a Horse Face

The Tibetan Deity with a Horse Face During my most recent journey to Tibet, someone pointed out to me in a temple a deity who bore a small horse upon his head. I knew that this protector is called Hayagriva, and that he is sometimes referred to as “Horse-Headed” or...