How the presence of goddesses paved the way for female power

One of the theses of my book Matriarchy in China: mothers, goddesses, queens and shamans (Madrid, 2011) was to assert that the presence of goddesses with prominent roles in a culture could signal the past or present existence of a matriarchal society. An interesting book (Rothschild, Norman H.. Emperor Wu Zhao and Her Pantheon of Devis, Divinities, and Dynastic Mothers) published a few years ago examines in detail that relationship on the occasion of the ascension to the throne of the only empress of China: Wu Zetian.

Empress Wu was the only empress in Chinese history to ascend to the imperial throne in her own right. Other empresses, more than the official histories tell, assumed directly or indirectly for many years the throne of China, sometimes legitimately, as regents, and sometimes through their influence over emperors without personality or too young, but the only one who can be called in her own right empress was Wu Zetian.

In fact, the time during which this woman directed the destiny of China extends beyond the time she properly exercised as empress, for during much of the reign of her husband, Emperor Gaozong, she ruled already in his name, and the two were known as «the two sages». Only at his death, she made effective a government that she had been carrying out during the last years of Gaozong’s life, but in order to cement the female presence at the pinnacle of imperial power in an eminently male-dominated country, in which all previous emperors had been men, the empress promoted a continuous re-evaluation of the role of some exemplary goddesses and mothers from the most remote antiquity. In this way, she placed before the eyes of the people, and especially intellectuals and ministers, examples from Chinese history in which mothers or goddesses had played a decisive role in the government of the country, the family or the salvation of the motherland.

This exciting book is a journey through these historically important female deities and mothers. By analyzing the relationship, and the exaltation that Empress Wu made of them, the author also tells us about their trajectory, the importance they had at a certain time, how they were subsequently seen throughout the history of China, and especially how they ended up being considered a suitable model in which to reflect the government of Empress Wu.

In this way the reader discovers again not only the true importance of some already known deities such as the creator Nuwa or the Queen Mother of the West, or the Goddess of the Luo River, but other models usually not so well known appear, such as the mother Wen, wife of the first emperor of the Zhou Dynasty, the mother of Mencius, the mother of Laozi, in some texts one of the supreme deities of Taoism, or Maya herself, mother of Buddha.

With all these deities, an atmosphere is created in which the presence of a woman at the helm of the country not only becomes normal, and therefore acceptable to all those involved in the government, but we could even say that it becomes a blessing. One that brings with it a whole series of positive feminine factors that lay dormant in the history of China and are made manifest with the empress.

It should also be noted that indeed, as happened in the case of some other empresses regent, Wu Zetian was concerned that this theory became a reality, and the years she was at the head of the government were really years of prosperity for the country.

The two great virtues of the book are to establish the importance of deities and female characters throughout history, sometimes latent or little studied, as well as to relate these virtues with the political history of Wu Zetian. A book that for the originality of its approach and the success with which it is carried out is recommended for all those interested in Chinese history, in gender relations in this country, in the matriarchal mythology of China and in the Tang dynasty.

There are two paragraphs that can perfectly summarize the book’s approach:

«To realign her culture’s mythic, symbolic, and linguistic concepts in ways that sanctioned her authority was a complex undertaking that included an adroit campaign to position herself as the scion of a powerful and virtuous female pantheon. Meticulously, she developed and embraced a lineage of culturally revered female ancestors, goddesses, and paragons from different traditions, all of whom were closely associated with her person and her political power»

«Wu Zhao was fortunate to have a large storehouse of goddess myths to draw upon. Susan Mann asserts that for a traditional culture that was ostensibly patriarchal, China possessed a wide-ranging, variegated repository of myths and folklore concerning womanhood.2 In her study of Chinese mythology, Anne Birrell remarks that ancestral goddesses like Nüwa and the divinity of the Luo River were “more mythologically significant in terms of their function and role” than their male counterparts. She notes that these female divinities play a variety of different culture-shaping parts: creator, nature spirit, local tutelary spirit, mother or consort of a god, harbinger of disaster, donor of immortality, bringer of punishment, and dynastic founder»

This work separates into four categories Wu Zhao’s assemblage of divinities and eminent women:

Part I. Goddesses of Antiquity

Part II. Dynastic Mothers, Exemplary Mothers

Part III. Drawing on the Numinous Energies of Female Daoist Divinities

Part IV. Buddhist Devis and Goddesses»

Ceinos Arcones, Pedro. Matriarcado en China: madres, diosas, reinas y chamanes. Miraguano Ediciones, Madrid, 2011.

Rothschild, Norman H.. Emperor Wu Zhao and Her Pantheon of Devis, Divinities, and Dynastic Mothers. Columbia University Press. 2015.

Last posts

Suicide Caused by the Sale of Wives in Late Imperial China

Suicide Caused by the Sale of Wives in Late Imperial China During the Qing dynasty, family relations were a constant cause of suicide, especially for women. Many of the distinctive features of Chinese marriage pushed women toward suicide, one of the most lethal being...

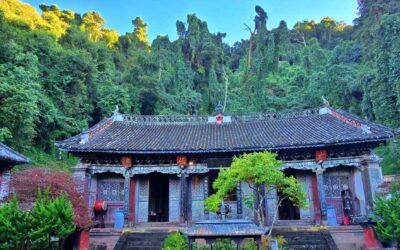

Discover the Treasure of Weibaoshan Mountain in Yunnan

Discover the Treasure of Weibaoshan Mountain in Yunnan Weibao Mountain (巍宝山) is one of the sacred mountains of Yunnan. Within its relatively small area it brings together a historical, artistic, natural, and monumental ensemble that makes it a unique place in China...

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven

Imperial Processions to the Temple of Heaven Those who know China—even if only through a brief trip—and who have visited the Temple of Heaven in Beijing will surely have been fascinated by the sober beauty of its buildings. Yet, whether on a crowded day or during a...