The Llubhu, women shamans of the Naxi

The llubhu (also called sunyi) are the Naxi sorcerers or sorceresses. In ancient days they were always women, mediums who went into trances and claimed to see ghosts, the spirit of the deceased persons. They have the power of dealing with ghost and demons, to cast horoscopes and to enter in communication with the dead. The pictograph for a llubhu depicts a seated woman with flowing hair; they were consulted to divine the causes of misfortune, to speak to the dead, and to drive out demons while in trance (Jackson 1979: 57). The name llubhu could also be translated as “wife of llu”; being the llu-mun the serpent spirits also known as Shu[1]. This could explain the feminine character of the llubhu as well as their ability to enter in communication with the spirits of nature.

Ladies of the night

Goullart (1957: 234) tells that the visit of the llubhu was always arranged in the middle of the night, when the neighbours were asleep. He chanted the incantations from the scriptures, accompanying himself on a small drum. He danced a little. Then he fell into a trance. There was no direct voice. The man gasped out what he saw. It might, for instance, be a tall old man in a purple jacket, slightly lame, leaning on a black stick. “Oh, that is Grandfather!” cried the family, prostrating themselves. Then the sickness of the patient was described. “The old man is smiling,” reported the sunyi. “He says the boy will recover in seven days if he takes this medicine”.

Sunyi is a disrespectful term for a llubhu, in which the symbols for blood and penis were used, which either hints at sexual orgies in connection with the worship of Sanduo, their patron deity, or could be insulting defamation. In fact, the term “nyi” means to heal or cure so it could refer to the healers of the mountain god; this is more plausible because of the close resemblance between the term sanyi and the name of the Yi shaman (Jackson 1979: 397).

Sexual division of religious tasks

In the old Naxi society there was probably a sexual division of religious tasks, with female shamans responsible for divination and male priests for ritual. Old Dongba manuscripts suggest that in the past women were considered smarter and enjoyed a superior position than men. They knew the essential divination techniques, they could choose the types of rituals in accordance with the results of the divination, and they were more often possessed by spirits than the men.

With the establishment of the male-dominated society divination and rituals were performed mainly by men. Women were banned from the public arena and religious rituals, and treated as if they were possessed by evil spirits instead (Xi 1999). In the real practice the activities of the Dongba and the llubhu are not clearly differentiated. Many Dongbas acted also as llubhu, performing a symbolic change of costume when they exchanged roles (He and Yang 1993: 191).

The llubhu also have their special ritual paraphernalia. They wear a long blue dress with a belt and a red turban; their sacred instruments include a sword, a small gong, some iron bells and rings, and a small drum hanging from their neck (Guo 1998: 326). They are not attached to Dongba Shiluo but to Sanduo, the divine spirit of the Jade Dragon Mountain.

The candidate to be llubhu must have the capacity for sustained dissociation or self-hypnosis if he is to carry out the exploits demanded of him: licking red-hot plough shares, dipping his hands in boiling oil and setting them alight, etc. Many llubhu get the power to contact with the spirits after suffering a severe sickness. Then they will perform a ceremony to get their red band. They dance as crazy towards the Sanduo temple, where they must continue dancing frenetically before an image of Sanduo covered by a long red cloth. The prospective llubhu keeps dancing before the image, and if the red cloth falls over him, it means that Sanduo god accepts him as a llubhu, if not, he will be considered a person with mental problems, being the red band their distinctive mark.

The llubhu of Tacheng district are known as sangpa, they have some power stones of brilliant quartz. They can perform divination and face directly the spirits that cause a sickness. To heal a sick person they go into trance and directly confront the demons, they “leap into the bonfire and with his bare feet scatter the burning logs into the four corners of the courtyard” or show their magical skills spreading boiling oil with their hand around the courtyard, or even killing a small pig biting its back (Rock 1924: 19).

In the old Dongba manuscripts there is no title for the Dongba, existing only the bimo or ritualist, the paq or diviner, and the llubhu or shaman. Dongba in Tibetan means teacher, in Naxi dancer; it suggests that at some point in history the Naxi dancers, i.e. the llubhu shamans and the bimo ritualists, whose functions were similar to those of the Yi and other ethnic groups, embraced the Dongba Shiluo mediation in their rituals, the central point of the Dongba doctrine, and all of them became Dongbas. All them were called “master” and considered wise.

As the Dongba were mainly responsible for ritual activities, they didn’t need to have special psychological or spiritual powers. When bimo and llubhu made the powerful Dongba Shiluo their own ancestor, they tried to guarantee the efficacy of their ritual independently of the individual power of each one.

Shamans who became priests

If these bimo ritualist farmers that were called after their day work to relieve the pain of their fellow citizens saw in the Dongba movement a chance to increase their efficacy, the llubhu shamans, always on the verge of a failure that could make them be considered crazy at the eyes of the people, saw in the Dongba mediation a chance to a socially respected position.

They were the best fit among the Naxi to understand the ideas that underlie Dongba rituals. There are Dongbas who are at the same time llubhus because many llubhus choose to become Dongbas, Dongba being an honorific name and not a name that denotes a specific religious activity. Other religious specialists, paq or diviners, could have followed the same path.

The Dongbas gradually displaced or converted other ritualists to their ritual techniques; in the end their efficacy was considered so high that they performed most of Naxi rituals. The fact that women cannot be Dongba explains that most of the paq were necessarily women, being the male paq possibly transformed into Dongbas. While the ritualist saw his power increased by the mediation of Dongba Shiluo, shaman and diviners saw their activities socially recognized.

The local adaptation of deities belonging to cultures considered more advanced is a common act in China and the rest of the world. While Chinese influence was focused in the Mu court and the Naxi aristocracy, with their Buddhist and Confucian temples and their Taoist rituals, the Bon wizards had the same effect in the isolated Naxi villages.

The people expected efficacy from the Dongba ritual, which helps understand that with the arrival of modern medicine they became diviners, or psychopomps, as today. This search for efficacy is shown in the first moments of the ceremony when the llubhu ask for the help of his protector deities, of his ancestors and even of the ancestors of the sick person, to get the power to heal (He and Yang 1993: 241).

Extracted from Pedro Ceinos-Arcones’s book “Sons of Heaven, Brothers of Nature- The Naxi of Southwest China”. BUY IN AMAZON

[1] Llu also means arrow and an arrow is used to symbolize Sv, the Life god; these two Shu and Sv are intimately related. The ubiquity and uniqueness of the Shu mythology in Naxi belief make it extremely probable that this was an ancient set of ideas connected with shamanism (Jackson 1979: 259)

Last posts

The tiger hero of the Naxi

The tiger hero of the Naxi[1] A long time ago, a man named Gaoqu Gaobo lived in the Baoshan area. He had a strong body, lively intelligence, and certain magical powers. He was always willing to help people. One day he went on a trip with a group of villagers. After a...

Wonderful- yaks most precious treasure is their manure

Wonderful- yaks most precious treasure is their manure Most of the travelers who visited Tibet in former times noticed the importance that, for the maintenance of the living of the Tibetan nomads and travellers, had the Yak manure, known among the...

Life of Milarepa, the hermit poet

Life of Milarepa, the hermit poet. MiIarepa is one of the most beloved religious leaders of Tibet. His story, full of unique facts, has been told again and again over the centuries, and if the publishers did not warn that this is the autobiography written by the holy...

The first description of the Religion of the Yi

The first description of the Religion of the Yi By Father François Louis Crabouillet in 1872. The religion of the Lolos[i] is that of sorcerers: it consists only of conjurations of evil spirits, according to them, the only authors of evil. Without being devout like...

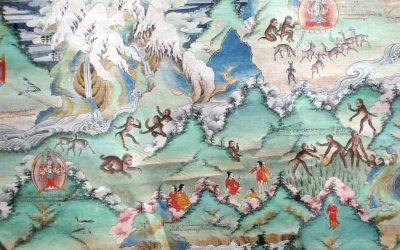

Tibetans, the people who descend from the monkey

Tibetans, the people who descend from the monkey According to an ancient myth, the Tibetans originated from the union of an ogress (raksasi) and a monkey. The monkey was sent by Avalokitesvara, Mother Buddha, to sow the seed of Buddhism in these lands. One day, an...

The sung funeral of the Kucong of China

The sung funeral of the Kucong Among the Kucong, one of the peoples who have most persistently maintained their isolation in the mountainous areas on the border of China and Laos, the different stages of the funeral are celebrated through music, which gives the...